Read in ಕನ್ನಡ.

I was born and raised in the Bantamale forest of the Western Ghats. As the evenings grew deep, Amma told us stories that we might forget the terror of the night forest. Darkness wrapped itself around us. Hear the Ribit-Ribit of frogs. The shriek of the Alu bird. There, as we trembled, in the small flame of the kerosene lamp which scattered no light, a story was born.

‘Long ago, in some village, a man was performing austerities. His name was Janaka Muni. In front of his hamlet, that was just like ours, stood a large tree. Each day, a black crow sat on that tree, cawing. This disturbed the rishi. Each time he shooed it off, the crow settled on another branch and began to caw again. Janaka Muni declared, “I will marry my beloved daughter, Siri Sitamu Devi, to whoever kills this bird!” Days passed, but no one came to kill the crow. One day, Ramadeva and Lakshmanadeva were in the forest hunting and heard about Janaka Muni’s promise. Lakshmanadeva surged forward, while Ramadeva followed behind. Lakshmanadeva looked at the tree, took aim and shot the crow. The bird fell to the ground. “Take our Sita”, said Janaka Muni. But Lakshmanadeva bowed his head and declined. “Siri Sitamu is not mine, but for my brother Rama”, he said. Janaka Muni did not agree and the two began a loud argument. Finally, Lakshmanadeva cupped his palms humbly and accepted Sitamudevi. He started his return to give her to his brother Rama. Along the way, Sitamudevi said to Lakshmana,

“The way is long and my legs ache. I need to rest.”

Lakshmanadeva agreed. He searched for a smooth rock, brought some tender leaves and spread them around well. Sitamudevi sat down on them, and slowly stretched out to sleep.

A strong wind was blowing that night. Off flew Sitamudevi’s upper garment. Lakshmanadeva shifted embarrassedly. He could not bring his hand to pull the cloth over her breasts. Finally, he knelt, and using his lips, adjusted her sari. Lakshmanadeva had become a child before Sitamudevi. Afterwards, they went to meet Ramadeva. On the way, Lakshmanadeva worried about whether or not to tell Rama the story of the sari. He told him anyway. “Don’t worry, I became a bird and was sitting on a tree and watching you” said Ramadeva.' The story would go on like this, and at some point, I would slip away into sleep. The next day, accompanying Amma into the Bantamale forest to gather bamboo rice, I watched the birds, trees, leaves, grass, the rocks, and recalled Rama of the night’s tale; all the forest turned into the Ramayana.

Years later, on the bank of a small stream at the foot of the Poomale hills near Sullia, I met an old man.

“Tell me a story, Ajja”

“Can a story be told just like that? Go eat, and get some sleep. Be up at dawn just as the cock crows, then I will tell you a story.”

Well, that’s what I did. When I rose in the morning, I saw Ajja already bathed, forehead smeared with ash, wearing a white cloth, sitting ready to narrate his story.

Is there a right time and place to tell a story, I wondered in surprise.

He looked at me,

“What are you staring at? I will tell you a story, and you write it, write, write it well.”

I collected myself and readied to take notes. Dawn is the hour when oral tales pass into writing.

Ajja began,

“O, Do you see all of that, the Poomale Hills? Do you know how it got its name?”

“No”

“Then write”

“Okay, tell me”

“A long time ago, Ramadeva and Lakshmana went with Sita to live in the forest. There, when she saw a golden deer, Sita was filled with desire. She was adamant about having it. So, Ramadeva went to catch the deer. When Lakshmanadeva saw that Rama had not returned for a while, he too went far in search of him. Meanwhile, Ravana came disguised as a sage, kidnapped Sita and flew off in his chariot.

‘Now, how to let Rama know that Ravana has taken me?’

Finally, Sitamma hit on a plan. She took off the flower garland in her hair and threw it down.

The place where the garland fell came to be known as Poomale Betta.”

“Now, Have you taken it down properly or not?”

“I have.”

Ajja’s story carried on till the sun rose. In the forest, Sita cultivated her jasmine flowers, sitting on a boulder she told her story to the wives of rishis, Rama caused the outlines of his feet to appear etched on a smooth rock… Sita gave her own name to some small birds. This is how Ajja’s story kept growing.

Later, whenever I roamed about Poomale, all I saw were the petals of the flowers Sita scattered. All I heard were the songs of Sita’s birds.

I noticed that as time passed narratives too changed.

In the 1990s, I was living in the coastal town of Uchila near Mangalore. One evening, a group of young men in saffron shawls came home.

One said,

“We plan to build a temple for Rama in Ayodhya. We are sending this brick for it. Take the prasad, make your contribution.”

“For which Rama are you building a temple there?”

“What does that mean? Aren’t you a Hindu? Babri Masjid is our land.”

One of them took out a small photograph and held it up for me.

I stared it.

It was a picture of a fearsome Rama, holding a taut, strung bow in his hand, rage writ across his face, different in colour, eager to kill. Rama, protector of all, appeared now as the destroyer of all. Gentle Rama on the tattered calendar, hanging on the wall of my hut in the Buntamale foothills, had transformed. The narrative had changed, I felt, watching the men’s body language and their language. Neither Amma nor Ajja was present in this new tale, not the birds, not even the flower petals.

Where are they now? Who must I write for?

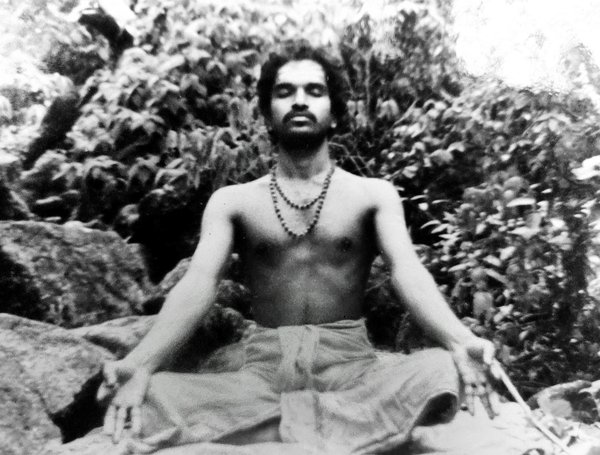

Purushottama Bilimale is a folklorist and literary critic who was born in Sullia, Karnataka. Dr. Bilimale has written extensively in Kannada on Indian Folklore, modern Kannada literature and is known for his thematic and formal engagement with Yakshagana. His major publications include Karavali Janapada (1990), Shista Parishista (1992), Kudu Kattu (1998), Bahurupa ( 2015) and Kannada Kathanagalu ( 2019) . He was awarded the Karnataka Folklore Academy award in 2008 and the Karnataka State award in 2011 . Purushottama Bilimale taught at Mangalore University, Kannada University and JNU, New Delhi. He was also Director (Programs) at the American Institute of Indian Studies.

Understory is grateful to Jayashree Jagannatha for her contribution towards the translation of this story.

7 September 2021