This article is abridged from Krishna Kumar. What is Worth Teaching?. Orient Blackswan, 2004.

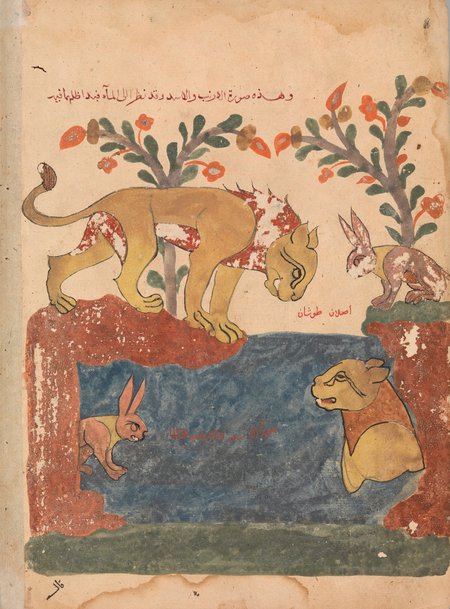

In an essay titled, Storytelling: What is the Use?, the educationist Krishna Kumar considers the value of traditional stories, and in this case, the well- travelled Panchatantra story about the rabbit and lion.

On the day of its turn, the rabbit appears before the hungry lion. The lion cannot think of anything else, but the rabbit explains why he got so late. He makes up a story about meeting another lion, and now the hungry lion grows angry at the thought of a rival. He wants to settle his rival first. The rabbit is not to be outdone and takes him to inspect the well where the rival lion supposedly lives. Peering in, the lion sees his own image and enraged, he jumps into the well, and to his death!

Why do children love this story?

Apparently, children have a great interest in grave matters like survival in the face of brute power and threat of certain death. Second, the little rabbit remains courageous and polite but employs a trick to get out of danger, a quality that also holds a young listener’s interest. Children identify with the hero who overcomes the source of their anxiety totally. It is hard to appreciate the morality of destruction, unless we perceive the child's anxiety. The Jataka stories, on the other hand, are stories of hope, unlike the Panchatantra’s stories of survival. Realization, rather than retribution, is the favoured narrative of the Jataka. Cleverness does not count for much; rather, it is the will to change and to see things differently, that creates the hope of a solution to the problem posed in the story.

What, then, do we gain from storytelling?

Stories need not have morals. Traditional stories like the Panchatantra are seldom interested in moral development. There are other gains of storytelling, however:

- Storytelling promotes good listening

- Storytelling trains us in prediction: listening to a story repeatedly gives a child the joy of prediction and inculcates self-confidence, especially when they begin to read. It attunes a child to rule-bound outcomes, as in mathematics.

- Stories extend our world

- Stories give meaning to words:

"Words are highly personal property, and the way words enable us to name the world is also highly personal. Yet, words are also a social wealth in as much as we use words to share our experiences with others. Meanings attach to words on account of this double-faced quality of words. For example, the child knows from personal experience what it is to feel hungry, but that personal meaning also helps the child to appreciate how the lion in the story must have felt when he was hungry. The story enables the listener to slightly stretch the meaning of the word ‘hungry’ so as to include the lion in it. The more stories one listens to, the more one’s vocabulary becomes capable of including in its orbit of meaning the experiences that others bring to us. Seen this way, stories told during childhood become precursors of reading."

Beyond Use

Instrumental goals do not do justice to storytelling. Instead, we might appreciate the diversity of cultural experiences and the oral competence and heritage that storytelling calls our attention to. While schools today focus on standards of literacy as a prerequisite to equal and democratic participation, those who depend on oral communication are referred to as illiterates, as unfortunate or handicapped, often considered an impediment to national progress. Yet, a great deal of life continues to present challenges that can only be met orally. Orality imparts directness and immediacy to human relationships which fosters democratic practice. Listening to a story temporarily places the child in an orally organized culture. Storytelling that is heard with pleasure and habitual attention to detail can also create an ethos in which egalitarian relationships can develop. These are good reasons to include storytelling in school curriculum.

Krishna Kumar is an Indian intellectual and academician, noted for his writings in the sociology and history of education. From 2004 to 2010, he was Director of the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT), an apex organization for curricular reforms in India.

18 May 2021