Part Two

Understory continues our conversation on reversing the anthropological gaze with V. Geetha, Editorial Director at Tara Books, Chennai.

Read Part One here.

Four

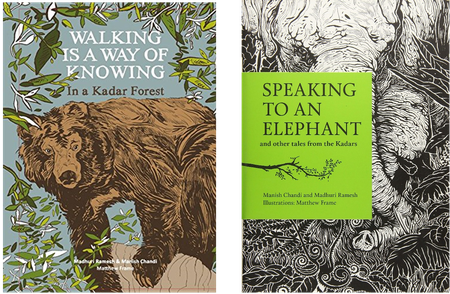

Tara Books makes an effort to remedy the ‘denial of coevalness’. One is with children, by providing quality, thoughtful literature. The other kind is with Adivasi communities. The two books on the Kadars bring this home, where adivasis who have traditionally served as guides into the forest, also guide the researcher and the narrative in the books. Such projects complicate the anthropological gaze. The editors of the important volume, Anthropology in the East, claim that, conscious of anthropology’s worrisome complicity in colonialism, anthropologists in India were “particularly concerned with ensuring the survival of India’s many tribal cultures and the protection of tribal peoples from exploitation by non- tribals, as well as their material betterment, education, and overall development.” They were also concerned about the enduring caste system, and many committed themselves to development programmes of the nation-state; for Nirmal Kumar Bose the objective was “to bring about justice where injustice prevails today. And this is where applied anthropology has a significant role to play and a heavy responsibility to bear.”

They note that many pioneering, scientific anthropologists also wrote a number of popular books including literary works. How has interpreting this tension between science and literature challenged your own work at Tara, and what do you think the future of anthropological thought and practice ought to focus on?

V. Geetha: We have been acutely aware of anthropology as a domain of knowledge ever since we began working with adivasi and folk/community artists. For, often, information and literature on communities is from within the discipline, and anthropological texts, we know, feature fables or art associated with them. One of the first attempts to create a discursive space for these art traditions in ways that cut through the anthropological gaze, was Jyotindra Jain’s Other masters: five contemporary folk and tribal artists of India. His other books, on the Kalighat tradition, on the great Ganga Devi, Mithila artist, and later on Jangarh Singh Shyam, pioneering Gond artist, and his Picture Showmen: Insights into the Narrative Tradition in Indian Art followed in its wake. These remained, though, within another disciplinary grid, art history, which, to be sure, they challenged. But that tension between being socially responsible and mindful while staying bound to one’s discipline, between cultural/literary/popular expressions and those defined by the discipline’s techne was not addressed in noticeably different ways.

The question, I guess, has to do with how we ‘present’ findings from the field: participatory research, autoethnography, politically supportive narratives and self-conscious texts, or those that address epistemic issues have all helped to complicate the relationship between the so-called field and our reception of it. But the very real material differences between those who occupy the field and us that write about them remains consequential: very rarely are the former featured as co-creators of meaning. A recent title, Jonathan Parry’s Classes of Labour: Work and Life in a Central Indian Steel Town addressed this conundrum by including T.J. Ajay as co-author. Ajay is not representative of the communities and classes that the book speaks of, but he is a literacy activist from the region, and extremely knowledgeable about various aspects of worker life.

As publishers, we have the advantage of curation: and so, we can both create space and context for varied points of view while holding them together within the book form. This is what we had done in Between Memory and Museum. Secondly, when we publish art or literature by those who are the field, we come in as book makers, and the adaptation to the book form is what makes for a unique mutuality, between creators and book makers.

With field work in anthropology, the tension that Anthropology in the East had wanted addressed between description/science and political judgment, or observation and literature, happens in language and argument. This can make for an understanding that can prove consequential, in an institutional and political sense. As when Virginius Xaxa is made part of a state-appointed Commission set up to address the problems of the scheduled tribes. Or as happened in the last century, Dr Ambedkar found himself part of the Starte Committee convened to enquire into the condition of the depressed classes and the aboriginal tribes in Bombay province (in the late 1920s). His sociological insights, experiential understanding and his commitment to conceptual rigour made for a unique sort of perspective, evident in the questionnaire that he prepared for field workers. Some writing has become part of political spaces, feeding into the politics of mobilization, dissent and contention. And this does not only have to emerge from within domains of knowledge recognised as such, by universities at large. There are other kinds of exchanges, as is evident from the life and work of ethno botanist Madhu Ramnath, or of ecologists working in different environments. I think here of the Save Western Ghats group.

Where the field does not transit into policy or movement spaces, and the anthropologist has to wrestle with words, meaning and forms of expression, the situation is clearly more fraught.

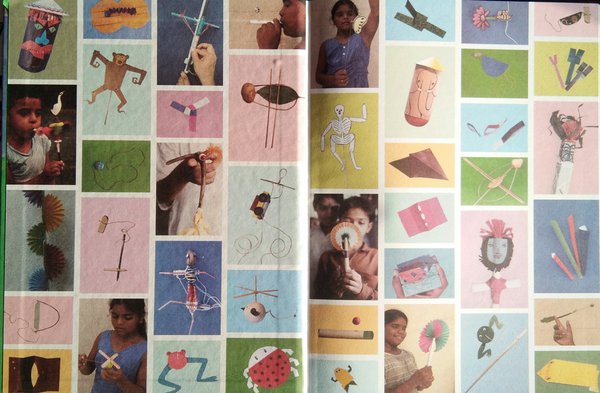

For us, to return to what I had started off in an earlier paragraph, it has been a vast learning process, and one that has unfolded through conversations, workshops, and continual practical work. I cannot overstress the importance of such work: when engaged in collaborative projects, and with a commitment to coevalness, there is much to give and take. The giving comes from our experience with the book form, and the taking from all that we are ignorant of, in an experiential and lived sense, but of which we are aware, in a textual and historical sense. The artists also experience this mutuality – and as many of them have told us, they are intrigued by book making and see it as an integral process, and many view the book as a valuable cultural object. The transformations required of their art to enter the world of the book, and the ways in which book making has to reassemble its processes to ‘make place’ for their art and worldviews: at Tara, we have come to these, in practical ways, through our experiments with the form of the book.

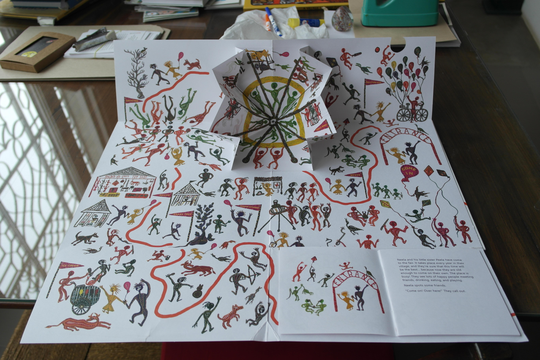

When we decided to publish Subhash Amaliyar’s painting of a Holi carnival (Visit the Bhil Carnival), we were loath to break his wonderful composite painting into blocks, or to edit it in ways that would make for a book. At the same time, we wanted to capture the happiness of that world, and the very many things he had put into it. So, our designer came up with a simple pop-up form that allowed us to work with a single sheet of printed art. But the problem of the text remained: we did not want the art and its context go uncontextualised, and we had a text that addressed children. The designer incorporated this into a small booklet that was then glued onto the printed sheet. This design is not the most optimal one, for such a project, but it is a useful example of how the form of the book is what constitutes the ground, literally and otherwise, for coevalness.

A more successful form is the one we adopted for The Deep, where we worked closely with two contemporary and young Warli artists to evolve it and here, we were able to stand testimony through our book making to their pioneering journey into art while they came to relish the excitement of putting their art between the pages of a book.

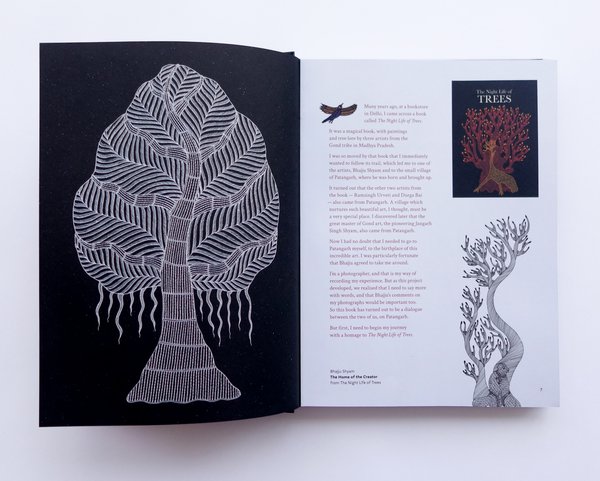

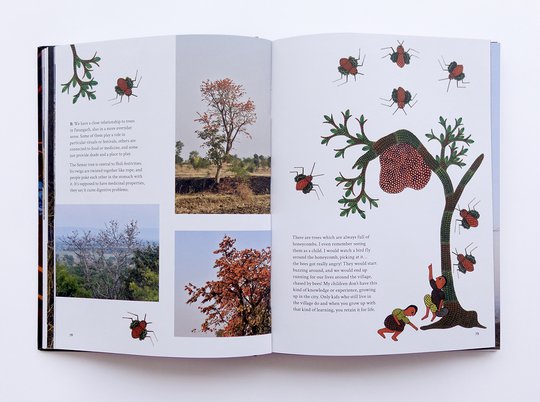

Less spectacular, but nonetheless visually exciting has been the design/form for Origins of Art: The Gond Village of Patangarh, where we feature Bhajju Shyam in conversation with Japanese photographer Kodai Matsuoka.

This was a conversation born out of wonder. Matsuoka was captivated by our title, The Night Life of Trees, and visited Patangarh, and took these amazing photos of trees in the village. We happened to see them displayed at an exhibition in Japan, featuring our books. And we thought there was a book in there, and decided to ask Bhajju to ruminate on Matsuoka’s pictures.

Meanwhile, we also worked out a narrative sequence based on existing photographs, and requested Matsuoka to take some more to flesh out sparse details. He did, and he also wrote his own impressions of Patangarh, addressing what he saw and experienced from within a Japanese cultural universe, with its own investment in craft cultures. Once the photos were all assembled, Bhajju spoke of each of them, and we then transcribed his interview and came up with a text that comprised his words and Matsuoka’s, arranged under different heads.

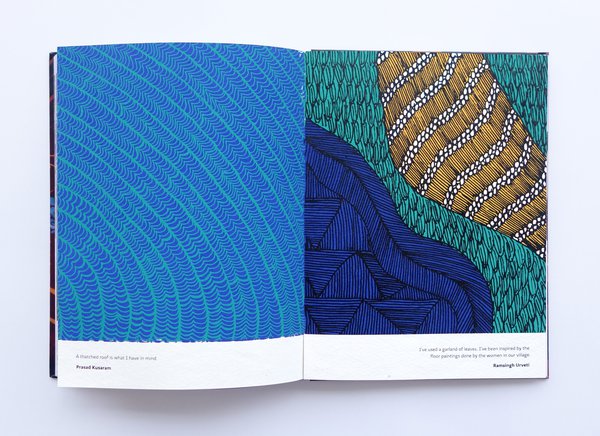

The designer, working with text and photos felt we needed more: to capture the artworld of the Gonds, of that village, and she came up with the idea of featuring extracts from such Gond art that we had already published. She was delighted to find that the art captured aspects of the Gond world that Bhajju and Matsuoka referenced in uncanny ways, and so incorporated it into the design.

Also, to indicate the specialness of the Gond aesthetic, which we had already paid tribute to, in an earlier book, Signature, she asked for a set of images from that book to be silkscreenprinted and bound along with the regular offset printed pages and cover.

This book features multiple conversations: between Bhajju and Kodai Matusoka; Bhajju sets up a traffic between memory and the present; and we place in dialogue, photos with art, and what Bhajju and Matsuoka say, with a reassembled Gond art universe.

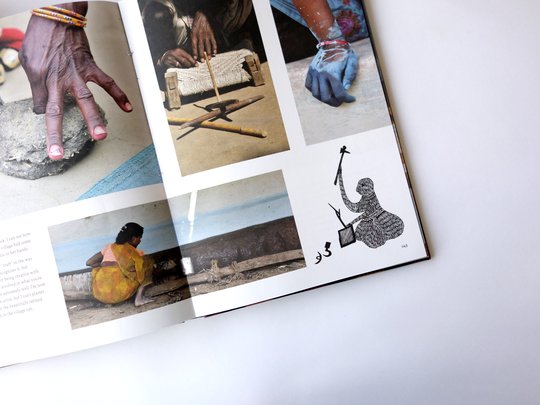

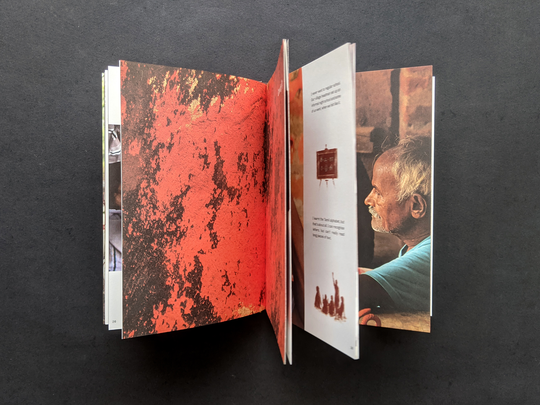

Tara has a new series, Makers, that will feature artisanal practices, and the first book is out: A Potter’s Tale, and here too book design provided the modality for us to bring alive the potter’s world and to flag it in ways that address a crucial absence in our understanding of artisanship: the artisan’s knowledge of his or her craft, and self-consciousness. Rather than dwell on modes of reception and transmission of modern ideas, and of the burden or relevance of tradition, we stay in this book with the artisan’s sense of his journey. The challenge has been, to both contexualise as well as render coeval this universe, with our own, without only foregrounding our concerns and questions.

In terms of what these exercises might hold for anthropological practice: I have no readymade answers, but I think collaborative creative labour that results in material outcomes, and is sustained over a period of time, holds promises. Such labour and outcomes might not be grandly consequential or enable political transformation in the sense we understand the term, but meanwhile, we will have something to show for our efforts: a book, an art space, a cricket team, a housing project, a women’s room…

Five

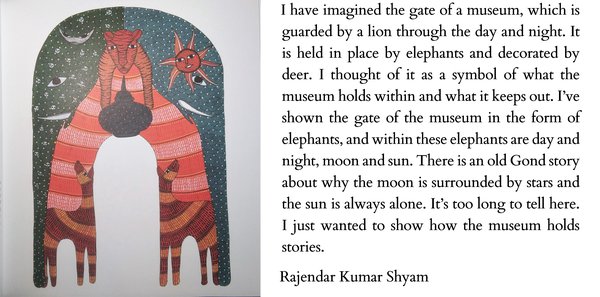

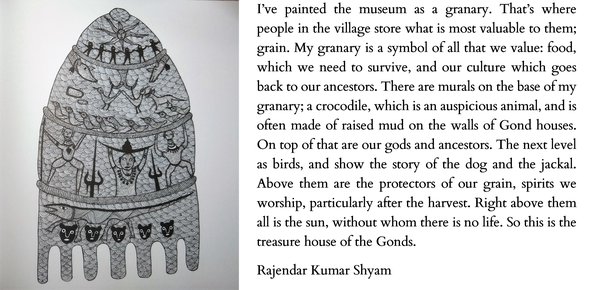

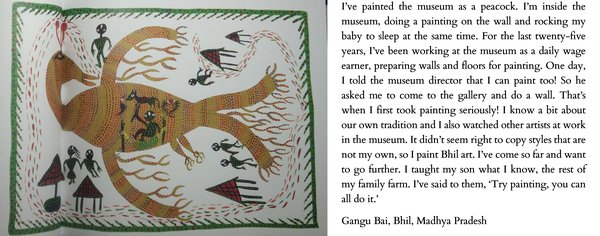

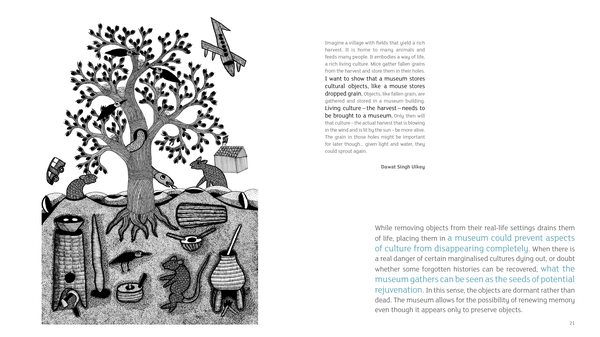

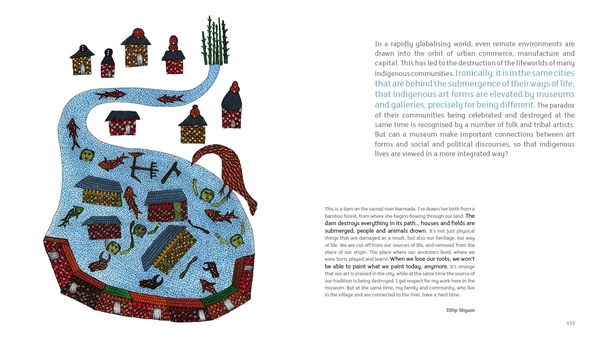

In Between Memory and Museum you say that “within the space of the museum, [folk and tribal artists] are generally spoken about or spoken for. What would happen if this classic anthropological gaze were to be inverted?” And the book offers multiple ways to answer the question. I was interested to see that, despite some ambivalence, there is an overwhelming endorsement of the museum through the artists’ recreated representations. The museum is a peacock, a goddess, a mother, a granary.

Among instances of ‘inversion’, the Ziegenbalg Museum in Tharangambadi recently invited artist Asma Menon to develop her own contemporary ‘cabinet of curiosities’ from her travels in Germany. I’d like, instead, to ask you about ways to think of autoethnography. I have in mind Zora Neale Hurston’s Mules and Men (1935) where, as Franz Boas’ student – as a Black female participant-observer- Hurston collected Afro-American folklore. Memorably, she describes her discipline as “the spyglass of anthropology”, indicating the detachment, voyeurism but also the productive cultural relativism that comes out of Boas’ scientific discourse. In her novels too, the scholar Karen Jacobs notes, Hurston contends with terms in currency then (“primitive”, for instance), but she deploys them to claim an embodied Black female actualized self, “She pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.” Reading ‘lies’, and the combination of ethnography and autobiography in Hurston’s revitalizing prose made me curious about what you think of the disciplinary purchase of autoethnography, given your interest in the anthropological gaze.

V.Geetha: Between Memory and the Museum is genealogically linked to Bhajju Shyam’s The London Jungle Book. When we began working on that project with him, he spoke of Elwin Sahib (Verrier Elwin) who had spent time in Patangarh. His grandfather had assisted Elwin, was, at that time, considered his ‘manservant’. Bhajju was rather tickled by the idea that here he was, all set to write about Elwin Sahib’s people. As he told us, “Elwin Sahib had written about my tribe, now it is my turn to write about his”.

This is what made us think of the anthropological gaze and how an artist or writer may return or invert it. Bhajju Shyam was scrupulous in his civility: he did not wish to judge, he made clear, because he was a visitor. Politeness required him to observe, comment, and not rush into articulating complete points of view. He could not of course desist from comment and critique, but equally, he was warmly affectionate towards the great city and its people.

His time in London began with the realization that he had “become a foreigner”: “I had seen foreigners before- some of them had visited my village to look at our paintings, but now I realised that something strange had happened. My colour was different, my language was taken away from me… I myself had become a foreigner”.

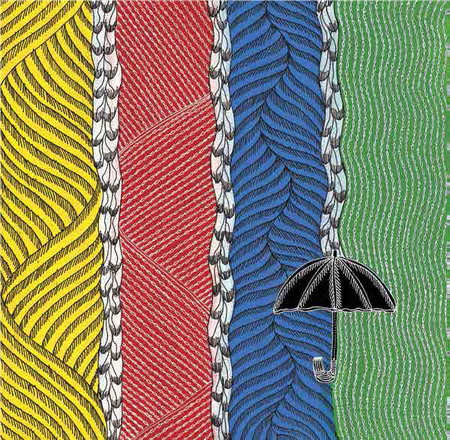

And, as a foreigner, his gaze turned quizzical and his art ended up defamiliarising the city’s well-known character. As he remarked of its rain and dampness, “Something is always falling from the sky” and he chose to interpret these ‘fallings’ in and through marks that derived from traditional Gond tattooing (which he described as the “only permanent marks of our creation which we carry with us through life and even after death”).

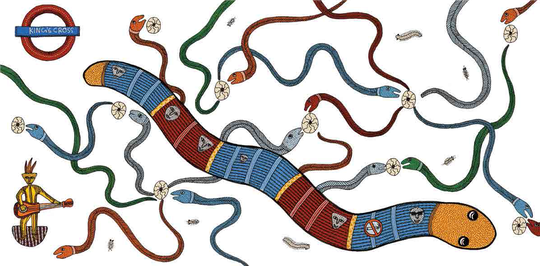

The London Underground seemed to him a giant earthworm, the king of the Underworld in Gond stories and he wondered whoever thought of getting people to “burrow underground because there is no more space in the world above”.

The English pub seemed a mysterious space, where miraculously as it were, the English people changed: “once they enter a pub, they look much happier and laugh much more, and don’t mind starting conversations with strangers”. They were like bats he thought who come alive at night and hastened to add that he did not intend to make fun of them, only to point out what the evening did to them.

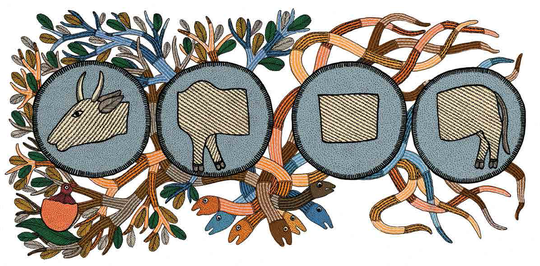

Perhaps the most ingenuous instance of reversing the gaze is to be had in his reaction to exhibits in a modern museum, where “a real cow [was] cut up and put into big cases with some kind of liquid in them. We have cows in the middle of the road in India, but not inside galleries”. The only time he had seen dead animals floating in glass cases was at the science museum in Raipur. He wondered what the artist wished to say with this installation: maybe something about death? Howsoever he tried to reason the artist’s motive, it seemed to him rather counter-intuitive: and so he reworked the spliced images of the cow in an artwork that embedded it within a Gond sense of the universe: “For us life does not end with death … every death is a new beginning. So the tree in the background is dying on one side, but is reborn on the other side, with new leaves and a baby bird hatching out of is egg…”

What is interesting about this painting is that it actually responds to another work of art, and on its own terms, and this, to me, appears significant. It is not so much a question of deconstructing and unravelling hidden – and untenable – assumptions about life, history or culture, rather for Bhajju, to talk back is to engage in a conversation, to rethink representation within the terms of another worldview.

I think this manner of addressing the anthropological case is somewhat different from the kind of autoethnography that is at play in Asma Menon’s Cabinet of Curiosities.

Bhajju Shyam’s art for the London Jungle Book provided us with an aesthetic context to think, along with him, on the relationship that artists like him had with institutions and individuals who sought to ‘represent’ them, or who wished them to ‘represent’ themselves in particular ways. Bhajju made clear that he was not to be dictated to: "I made a painting with a bicycle in it, once…drawn in the Gond style. Some artists in Delhi got at me for it… ‘Why are you drawing modern things? There is no steel in your village-how can you draw a bicycle…’ They forget that we have bicycles in the village now. And how come they have the right to paint anything they like, but I must stick to wild animals because I am a tribal? ... That’s not to say I’ll throw my tradition out. I can’t – it’s in me. The new is done with the old in my blood”.

If we are to read the responses of artists to the museum as an institution, in light of Bhajju’s views, it is evident that they do not wish merely to speak of the museum as a space that objectifies and exoticizes their work, lives and histories.

They are keenly aware of what time does to memory and objects, and how the claims of a collective understanding of culture and the past could well remain rhetorical, if the material evidence of that past vanishes.

Also the present is not the best possible place to be in, for some of them, and to survive and draw on memory and traditional practices is a fraught as well as necessary exercise, which however requires an anchor of some sort to sustain itself.

As they ‘drew’ and ‘represented’ their relationship to the museum, we realised that their art is not just expression, or even representation. Rather it is, itself, a form of knowledge about memory, survival and history. And here, lines, colour and symbols and their combination speak in ways that are not always matched by words. I am not sure if art in this context is ‘autoethnographic’, in the sense the term is usually understood.

For one, it was ‘solicited’ in that we framed the argument, to which the artists responded. While the original impulse for thinking on these matters owed to Bhajju’s deep interest in these matters, we had since gone about working in ways that we were trained in: reading up, visiting other museums… Further, we also had to stay honest to our sense of the museum: as an essentially colonial and problematic institution. Personally, I had come to this critique through a reading of Andre Malraux’s Museum without Walls. I had known the book for nearly two decades and more, but now had a chance to review its content in another historical context and place.

Secondly, the occasion for doing this book was created by the museum, to which many of the artists that write about the institution are attached, in one way or another. In that sense it was a gracious if somewhat unusual gesture: that the museum bureaucracy was willing to countenance reflective thought on its own existence.

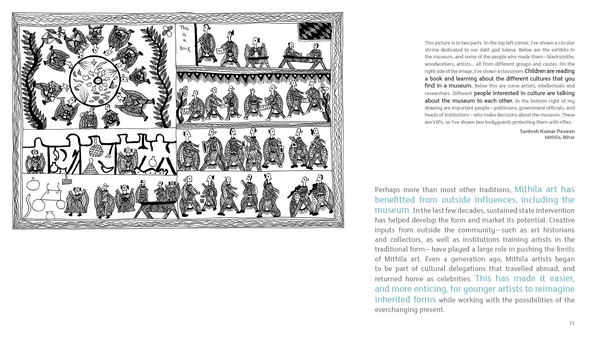

Thirdly, as publishers, we played a role in shaping the book and its content: this is evident in the book design. Every spread of the book comprises three elements: our commentary in larger font, the artist’s work, and her or his views, which are styled as captions/annotations. Art and caption form a unit, but each could also be ‘read’ on its own. Our text works as epigraph, heading and masthead that leads the reader from one argument to the next.

The art and artist’s voice as they feature here, therefore, are part of several moments: of thought, practice and organized communication. To read them in the context of debates within anthropology, to do with voice, location, power and politics can be productive. Equally so, would be readings that take off from the art and the artist’s world view. While this latter provides a contextual explanation for what has been depicted, the depiction is never entirely at one with it. Or indeed with the artist’s feelings and views. In the doing, another element is brought into play, and this cannot be understood in terms of reflection, mirroring, or even self-expression merely. The imagination, as it emerges in the doing, is ultimately irreducible. Hurston’s prose is its own thing, and owes as much to her love and felicity with words as it does to what she wished them to say and capture.

In this excess of semantics that will not be ordered easily lies the hope of another point of view.

***

V. Geetha is writer, translator, social historian, activist, and a leading intellectual from Tamil Nadu, India. Among her notable books are Gender (Stree, 2002), Towards a Non-Brahmin Millennium (with SV Rajadurai, Samya, 1998), Undoing Impunity (Zubaan, 2016) and Another History of the Children's Picture Book: From Soviet Lithuania to India (with Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, Tara Books, 2017). Her Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar and the Question of Socialism in India is forthcoming from Springer. In addition, Understory would like to acknowledge Geetha's generosity in accepting our invitation and her engagement in collective thinking, particularly with students.

5 November 2021