V. Geetha,

Tara Books

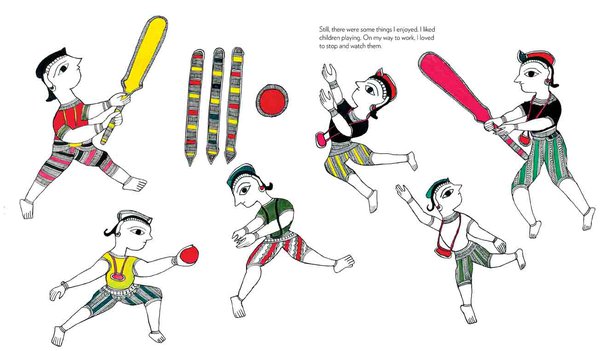

The 'Anthropological Gaze' is a way of seeing - it is an epistemological encounter - predicated on the distance between the ethnographer and their subject. The camera, for instance, studied people closely in the colony, sometimes staging them as exotic, at other times extricating people's bodies from their surroundings to frame particular features. Such documentary, with its scientific impetus, produced the self and the other in dramatic and haunting ways.

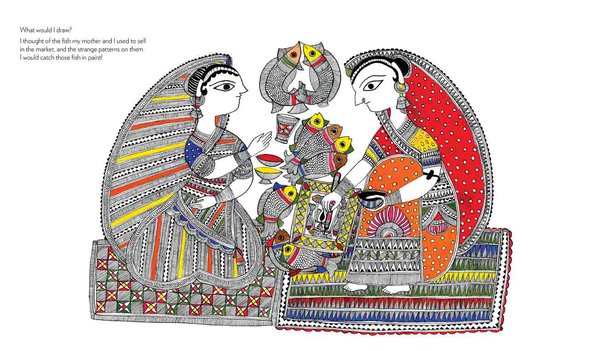

Tara Books, a Chennai based publisher, has sought "to reverse the anthropological gaze" through its pioneering engagement with folk and tribal art in its visual and handmade books. Reading, and returning to, these carefully crafted and densely suggestive books, the reader is in rapture: a feeling of both ecstasy and violent 'abduction' towards new possibilities. We spoke with V. Geetha, Tara's Editorial Director, about certain elements of their project: art education, imagination, emotion, and coevalness.

This is Part One of our interview. Read Part Two here.

One

My first question is about pretexts, and I want to begin with a play that you’re probably familiar with: Girish Karnad’s Naga Mandala. At the end of the play, Karnad provides a note about the folk story that inspired the work, and which he heard from AK Ramanujan. He writes that in the play, the empty house is a metaphor for the joint family, and the husband and cobra are how women in these families see their husbands: stranger by day, lover by night. When I read the play, that reading did not occur to me, and it frustrated me that I did not perceive the metaphor.

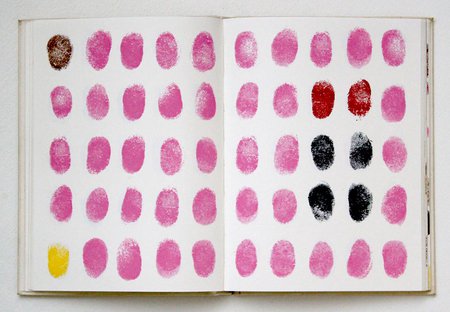

You provide a similar reading in Fingerprint, which is otherwise a picture book,

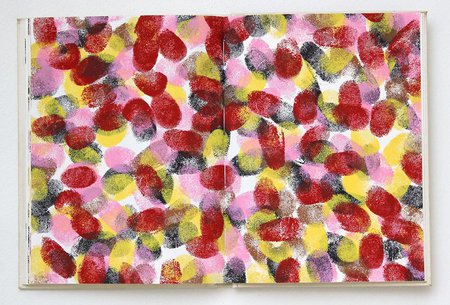

"Housed in a book, though, fingerprints appear transformed. Fading, bright, firmly marked on the page or delicately tattooed, a print acquires another life. Like words that won’t stay in place, or stay still, fingerprints wander across the page, enter into relationships with other prints, randomly, by design, and assent to being part of a series of relationships and patterns. These colour patches thus achieve a mobile effect, as they force the eye to look and re-look what appears a mere smudge.

There is a child-like lightness to these prints – they are almost edible, like boiled sweets, but when observed closely, the dried-blood smudging, and runny grey seem ominous. For the fingerprint in every instance is a mark of illiteracy or haplessness. It is what people offer in lieu of a signature, and what is forced out of them, when they are suspected of being outside the pale of the law; or when they are made to feel their very existence is illegal. To be fingerprinted then is to be stigmatized, rendered powerless. In some instances, it signifies mute acknowledgement – of being a subject-citizen, of assenting to a law or a decree one cannot hope to thwart or resist."

Looking at these images, I want to ask you about how you approach art education at Tara. Is art to be ‘interpreted’? Is there a veil to be pierced to get at meaning? Or do we stay with the surface, treat the (text-)image as an invitation and makes connections freely? Could you take us through two panels of your choice and talk about the way you understand art and narrative in them (for instance, you’ve spoken before about the highly condensed way in which narratives are depicted in some folk art).

V. Geetha: Many years ago, after the first of many workshops that we have organised with illustrators these last 25 years, we published a book titled, Picturing Words and Reading Pictures (1997). Part-manifesto and part loud thinking, the book featured work from this workshop, along with illustrators’ views on their art and the book form. Gita Wolf wrote a set of short essays, each of which explored the relationship between image and word. The questions that the book raised, and sought to address, have stayed with us, and we have gone on to extend their meaning and to frame them in different ways.

Here is a brief summary of the book’s central arguments:

- Book making is essentially a collaborative activity, with author, illustrator, designer and the printer/producer coming together to make the book.

- Words and visuals are integrally linked in the illustrated book: the “dialogic play between words and visuals gives rise to a creative tension” that characterizes its grammar.

- Illustration is not bound to words, as is sometimes imagined; equally, “a ‘dead’ book can be brought to life through illustration”.

- Likewise, words are not merely captions, or descriptions of the image, rather “…words can change the perspective on a picture”.

- A designer is not a technical expert merely who puts words and pictures together. Rather she “is the final presenter of the book” and “controls the way the book communicates”.

- Paper and the printing process, tactility and the form of the book: these also add to meaning.

- An illustrated book is not to be seen in developmental terms, as something that only little children read. It is possible to conjure up imaginatively rich visual worlds for older children and adults as well.

- Innovative and boundary-breaking illustrations can push back at familiar and easily consumed visual cultures. Reworking traditional forms, while staying sensitive to contexts, might help produce interestingly hybrid art that is more than style. Likewise, folk and tribal artists creating visual expressions of their worldviews can make for a truly alternative visual culture.

We started out from here, and have gone on to enrich our understanding of what pictures do, and how words work. And all along we have understood the relationship between art and text, image and its possible meanings as not something that is given by either, rather it is to be intuited through ‘reading’ pictures and words. The book becomes the stage, the arena where this reading unfolds.

In the case of Fingerprint, Andrea Anastasio was possessed by what he had been witness to, the power of the state to both demand your identity as well as mark it as problematic, unless proven otherwise. He had obsessively filled page after page with fingerprint patterns, as if he wished to conjure away their significance by coopting them into another narrative.

We did not want to ‘explain’ what he had done. On the other hand, we were wary of it being read as only 'design' and 'art' and consumed as such, with a genial gesturing towards its politics and context. It is not that we wanted to foreclose such a reading. But in our understanding, an image or a picture is not simply a mark on a page, rather it is framed by the context of its emergence, and without reducing meaning to its constitutive moment, we yet wish to indicate its relationship to place and time, in the hope that this helps decipher the image in a founded manner.

The question is, how does one provide context? The author's text can do this, of itself. Where it does not, a publisher's introduction, a caption, an end-note, even a blurb… we have worked at different options to mark context. And in each instance, the context-marking text does something different: it provides historical depth, recalls a long forgotten tradition of doing art in a certain way, calls attention to what the artist has done with the grammar of her art… But at all times, it provides a cue or cues to read the pictures, without taking away from the freedom of reading; the cues merely point to how the image is not only on the page, but is also part of the world.

So, if you are to consider the two spreads that you have chosen from Fingerprint: they comprise different sorts of prints, arranged in a certain pattern. As editor I did not want to offer a reading that was definitive, rather I wished to identify that the smudges on the page are related, and that this relationship is waiting to be 'read' in certain ways. In writing what I did, I followed the pathway of my responses, and accounted for them in terms of my politics and also history. In doing so, I did not stray away from the artwork, even as I brought in context and conjuncture to help me parse it.

As for the third image that you have chosen, it is not glossed as such, but by the time you get there, you have a language to read it with, and which provides you with a lexical direction that you can either pursue or from which you can wander away as well ….

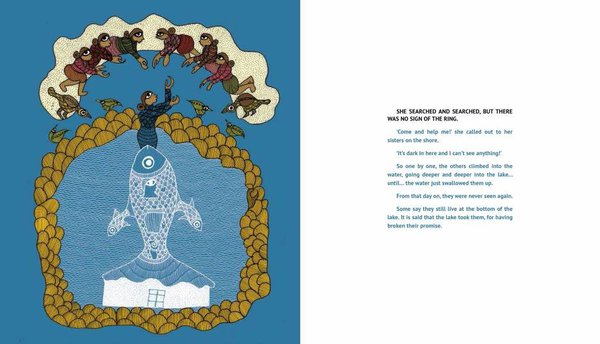

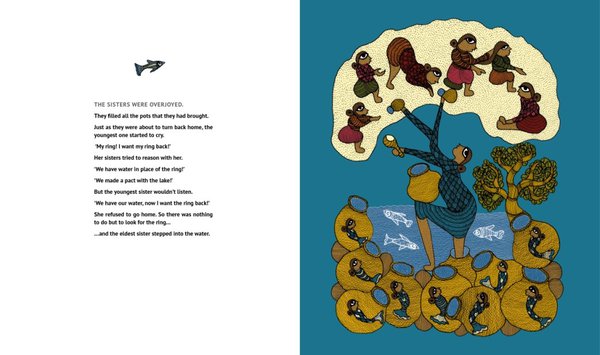

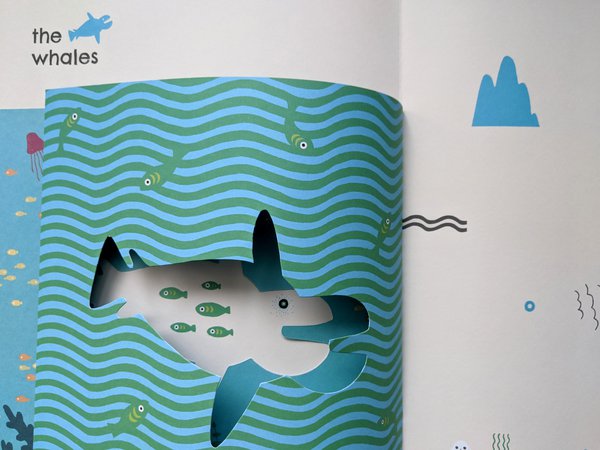

So, as far as “interpretation” of visuals go, we suggest how you might go about making sense of images, but we do not prescribe their meaning. In fact even in books where the text is solidly referential, the words do not quite exhaust the meaning of a page, or an image, or, for that matter, its content. Take this page from Water: the image is both illustrative and not, it references what the words say, but also hints at other meanings, situates the action in both ‘real’ time and in ‘fable’ time…

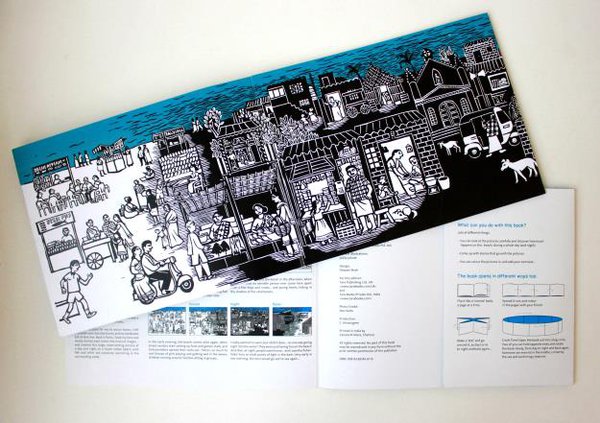

In effect, the visual literacy that our books build and provoke in the reader hinges on looking and re-looking, staying with the page, and being led by the image, as by the text. We have also done more or less wordless books, but even here, we provide context, though this might not be part of the narrative – as with An Indian Beach. Contextual information here is presented as a set of definitions and instructions that help to situate the book for the child, and the adult.

Sometimes the form itself helps contextualize the book, as with Knock! Knock! . Each page, as it opens out, takes the plot ahead. Equally, it asks the child to linger and take note of what is on the page. And we realise that the book is both about a child searching for a lost teddy bear, as well as a tangential invitation into a visual world, which contains many nested cultures. A book such as this can be relished by both child and adult.

Two

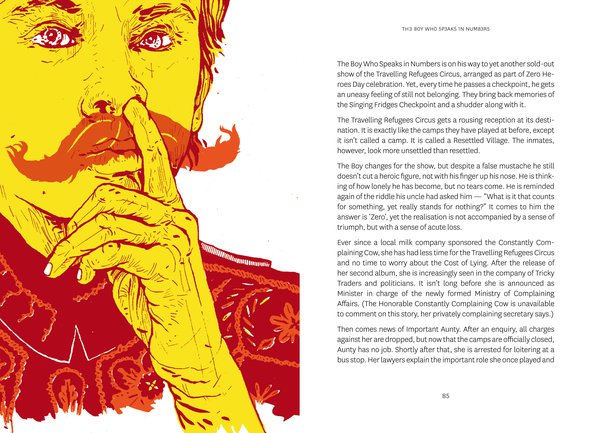

My next question is about imagination. In Mike Masilamani’s Th3 8oy Who 5p3ak5 1n Num83r5, the Sri Lankan Civil War is told from a child’s point of view, and the child processes the world through numbers,

… he knows he can count on the numbers

The same numbers that witnessed checkpoints come and villages go up in flames, cows who complain and lizards with bad breath.

The very numbers that met with Important Peons and an Aunty who scolded in rhyme and no reason.

The numbers that watched the Boy escape landmines and the Little Tin Soldiers – only to get bowled out in Cricket

The numbers that were by the side of the Boy at the Travelling Refugees Circus.

He knows the numbers will have the last word.

Reading the book, I was reminded of two things about the imagination from a fragment by Walter Benjamin. One, that the imagination works to deform (not to produce, as I had assumed). The second is that fantasy which resides at the margin of the imagination is both grotesque and constructive – it overforms. It seemed to me that The Boy deforms the world towards a hopeful future. Benjamin says of de-formation,

First, it is without compulsion; it comes from within, is free and therefore painless, and indeed gently induces feelings of delight. Second, it never leads to death, but immortalizes the doom it brings out in an unending series of transitions.

In another essay, Benjamin talks about how children learn from bright colours, which evoke memory without yearning. Without making a hard distinction between children and adults, it is hard for me to think of adulthood without "yearning and regret". What struck me about a difficult book like Masilamani’s is that it can speak about war and violence in this way – that it deforms state power and approaches conflict without regret. How do you think of imagination and fantasy in the children’s literature that you publish?

V. Geetha: I must confess I – and I guess, we – do not "think" as such of imagination and fantasy, as these feature in our books. We respond to the author/artist’s words, lines, colours, and in that response perhaps lies elements of our ‘thought’ on these two fascinating aspects of creation and expression.

Imagination has been understood variously, as we know. An early understanding, which I encountered in a classic text that we were recommended to read in our undergraduate English Literature classes (in the 1980s), distinguished the mimetic from the illuminative imagination. This was in M H Abrams The Mirror and the Lamp: Abrams viewed mimetic works of art as turning a mirror to nature, and imaginative, romantic expressions as illumining the natural world. And in this context, another definition or rather observation about the workings of the imagination that stayed with me was the one that John Keats referenced: the imagination as an exercise in what he termed negative capability. Not so much self-expression as receptivity, the taking in, of the world.

Imagination, for me, therefore has been an enactment of creativity, and it is not so much what one produces, but what I guess one marks out, unsettles, disrupts, or to use Benjamin’s words, deforms and overforms… and Benjamin’s perception, honed in the context of discussions of the relationship between the work of art and the so-called natural and empirical worlds, calls attention to a relationship, to how the work of art, or the text tilts the world, for the child, and for adults.

As far as the child’s world is concerned, an author/artist intuits it: through genre and form. At a time, when a child’s comprehension and relationship to words is increasingly determined through the notion of ‘competencies’ (not competence, as in generative grammar), such intuition calls out to the child reader to sojourn in a world that is not to be measured or ‘understood’ but relished, and wondered at.

I give below three ways in which I account for imagination and fantasy in children’s literature.

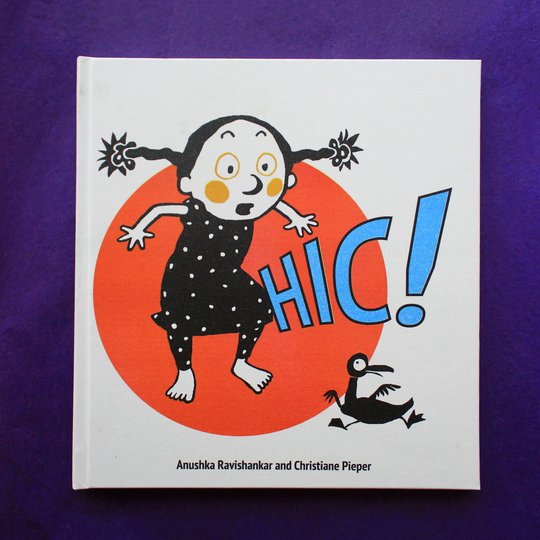

Anushka Ravishankar’s play with genre and language, with nonsense rhyme and absurd verse: she draws the child in, even as she appeals to the child’s sense of the quirky, through a brilliant overturning of meaning that is yet logical. When the villagers who have caught a tiger reasonably ask what they might do with the beast, several suggestions are urged forth (Tiger on a Tree):

Send him to the zoo?

Stick him up with glue?

Paint him an electric blue?

In Excuse Me, Is this India?, the images came first. Anita Leutwiler, a quilt artist from Germany visited us, and she did these beautiful quilts of her impressions of Chennai city. We invited Anushka to write verse to these images: each piece of textile art was exquisite and besides made up of bits of cloth Anita had sourced while in the city. Many of us had actually given her pieces from our homes, including old saris, dupattas, old sheets and so on… the images were thus laced with memory though we did not quite look at them that way, except to identify the piece of fabric that was ours!

Anushka decided to let the images speak for themselves, and focused on the experience of travel itself: on the unexpected, the strange, the riddling … in a sense like Shaun Tan’s The Arrival. And she did this through funny, logical and gnomic verse. And once again, we have logic that serves improbable scenes and situations sustaining the imaginative and the fantastic …

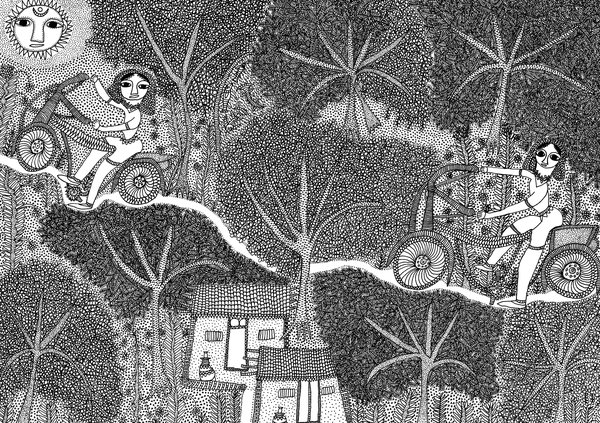

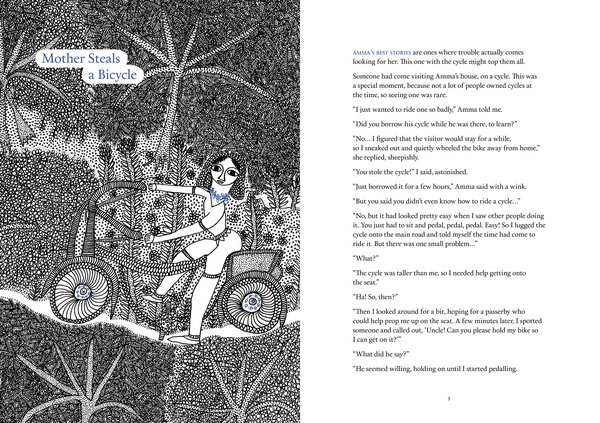

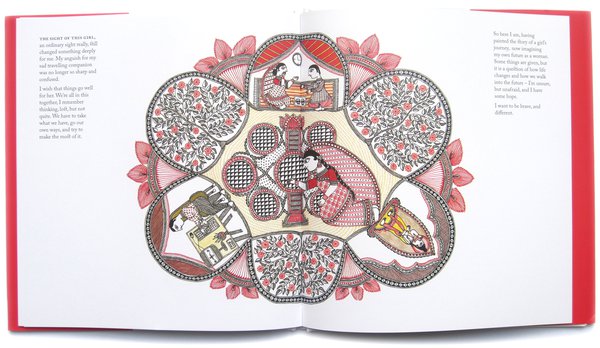

In Mother Steals a Bicycle, Salai Selvam builds stories drawn from a mother’s memory of her childhood. Childhood is reconstructed in interestingly political ways, in that the physically active and curious girl child is the one who has all the adventures. These stories are ‘narrated’ to a child by a mother, and that pedagogic transfer renders the past both relevant, meaningful and present… remembering childhood becomes an important act of constructing a new lineage of story-telling, from the mother to the girl child in a way that could not have happened, before the advent of feminism. The imagination/fantasy at work have to do with another way of living and being, and which is recalled not so much as an index of what the city child does not have, but as a sign of what a mother could be. And a child’s universe is deliberately reconstructed. Not that these experiences are imagined, but they are recalled to a purpose.

Imagination and fantasy feature differently in books that draw on the oral tradition. In Water, Subhash Vyam’s narrator recounts a tale where in return for water from a lake, a thirsty girl surrenders her favourite ring, and she and her sisters get to assuage their thirst. Predictably, she wants her ring back, and leaps into the lake. And she does not come up. Her sisters follow her, one after another… till there are none. The narrator admits that this story did not make sense to him as a child and that he was left with many questions: was it bad of the girl to want her ring back? Why was the ring so precious to her? And why did the lake that was kind enough to give them water turn punitive? And since there were no actual answers to these questions, he told himself that the sisters were living at the bottom of the lake.

Water is not quite a child’s book, yet the narrator’s musings grant us a context to consider how an uncertain and almost dystopian end to the tale might yet hold possibilities for the child. Given that this is an oral tale that was repeated over and over, it is likely that it enables the imagination to form, deform and reform… and it seems to me that in oral literature may be found elements which perhaps pertain to the child’s imagination, for these are always freshly "remembered" and "without yearning" – for the past is never truly that, and nostalgia is rendered impossible because the previous is not "lost" rather it is renewed and remade…

Yet there are limits to this, and in some instances, the past has to be put away, in a chronological and historical sense: when we worked on a resource book for teachers of Tamil in the primary classroom, we put together tales that children were currently listening to, across Tamil Nadu. We had a researcher going to different parts of the state, and eliciting stories. We thought we would use these as points of departure for teachers to start conversations in the classroom, and to draw out the children’s linguistic skills and intelligence. But the stories were of course steeped in caste and gender notions that were objectionable and we had to rework many of them, without injury to their narrative grammar or linguistic sharpness. So, oral narratives in themselves do not really offer us ways of intuiting a child’s world, or indeed of appealing to a child’s imagination, but they certainly possess elements that correspond to how children experience the world, of objects, animals, plants, people…

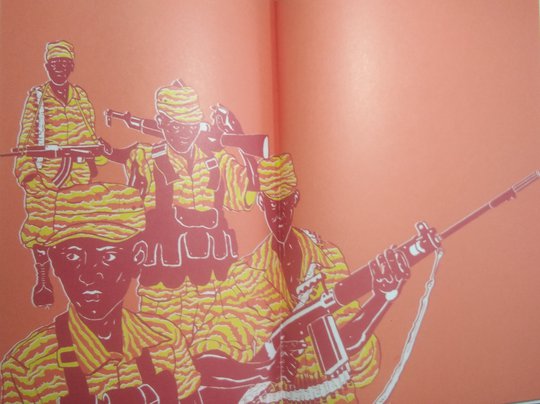

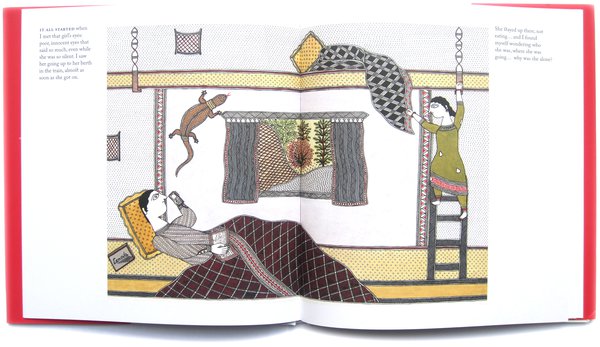

Now, coming to The Boy… we worked over several versions with Mike Masilamani. The original text was a playscript and had been performed in Sri Lanka and here as well. When Mike came to us with it, we discussed how it might be reworked so that it becomes a crossover picture book, one that can be read across ages. The problem for Mike was to end the book on a note that was neither cynical nor falsely hopeful. With the play, the performance and the contexts of staging helped to fashion meaning on stage: fantasy and satire became the vehicles of political commentary. For the book, we had to think of other strategies…

The child protagonist would obviously draw older children into the plot, but then he was not ‘any’ child: he was abled in ways other children were not, and this made him special as well as different. And this made for a tangential perspective that helped to complicate different sorts of polarities that existed in the Sri Lankan context: between Tamils and Sinhalas; the state and the rebels; the rebels and the people; the rebels and the soldiers; the war profiteers and the people… and it also pointed to the absurd, menacing and dangerously consequential power of the state, yet the state was also framed in terms of a war that it could not anymore determine entirely… Given the power of this slanted vision, the child’s character had to be realized in clear cut ways, and so we ended up paying attention to his use of language, and his understanding.

In any event, Mike’s deft and lightly held mastery over words effortlessly transformed cognitive dissonance into subtle and logical political commentary. And the child’s differently abled status did not emerge as such, but remained the very stuff of childhood, as it was experienced in a time of displacement, war and violence. The transition that the child experiences, from the village to the camps to the circus… this is mediated by memory, yes, but there is no nostalgia, rather there is a desire to be reunited with persons, beings, and it is relationship that the child seeks at all times.

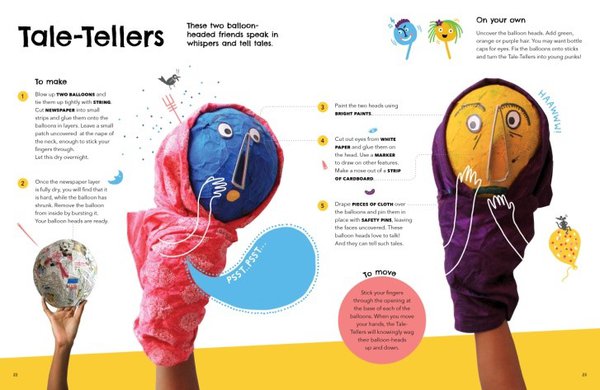

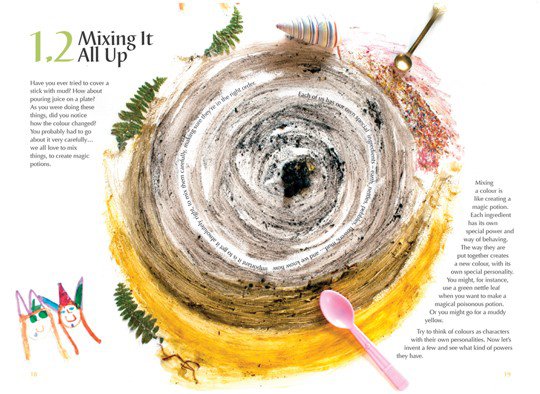

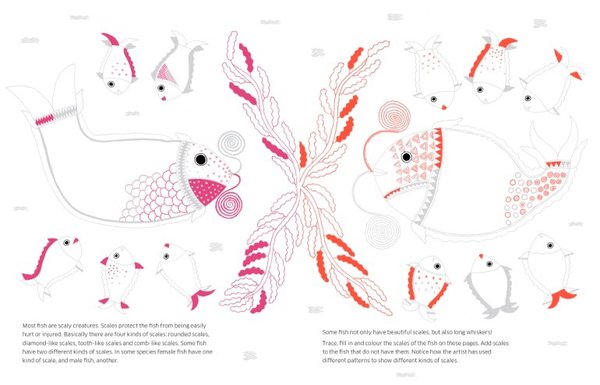

On an entirely different note: thinking of your remarks re: Benjamin on colour and on the imagination that does not destroy… It seems to me that in the way we do art pedagogy, we invoke the imagination as something that is experienced and realized in the doing. Whether it is the 8 Ways series, or Puppets Unlimited or Twins, or The Colour Book: the fantastic, the whimsical and the ludic co-exist and further are aligned to the pedagogic, and in this sense, call forth to the child, to imagine and fantasize, create and re-create.

Three

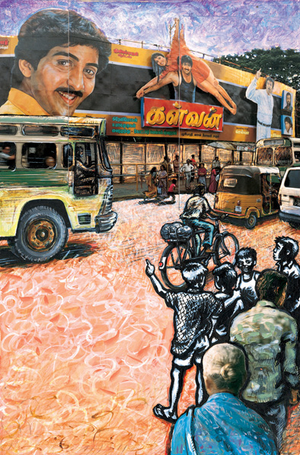

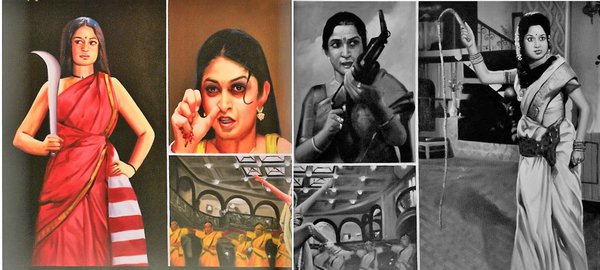

I want to ask about the ways in which you have explored and de-naturalized emotion in your books. In The 9 Emotions of Indian Cinema Hoardings, you quote from the Natyashastra: All art is a product of artifice, and use it as a frame to depict public, cinematic/aestheticized emotions. There is a certain interiority that is also operating here because emotion is entangled with a spectator’s memory – it has to be evoked. There are sophisticated treatments of emotion as well (eg. the Tamil akam-puram genres, the work of Margrit Pernau and Charlotte Vaudeville). Still, Tara’s David Days Mona Nights came as a surprise, with its ability to convey myriad feelings in a sustained, reciprocal way (the book has no page numbers, so the reader is immersed in the exchange) through letters between young adults.

My favourite lines from the exchange between Mona and David are, “Mona, don't think I'm not taking it seriously. I just can't say too much about it simply because I find that you're right.” They condense self-consciousness, awe, relationality in a way that might speak to someone who finds themselves in an unfamiliar but interesting situation (like a fieldworker?).

So, it seems like emotion is a shared, cultural expression, but also a kind of intelligence to be developed between people of all ages. How might such, and other, iterations of emotion feed into children’s literature?

V. Geetha: Emotion as shared intelligence: I think this is an important consideration for the editor, designer and curator, whether of books, images, ideas. While assessing the communicability of a text or art, we find it useful to ask the following questions: what assumptions are at work here? Is the text or art context sensitive? What would make for its transmission across cultures?

With regard to emotion, these questions translate thus: is a character’s sense of wonder, curiosity, fear, dread, and mischief expressed as an unmarked class or caste feature? Or does it answer to a shared experience of any of these emotions? If it appears an unexamined ‘class’ or ‘caste’-related expression, how might we bracket it, call attention to it? On the other hand, what is the advantage in featuring a class and caste-marked expression?

When books feature animals and birds, the question of shared emotions acquires a particular resonance: how do we ensure that animals are not cute or horrid human beings in disguise? And yet, how might we communicate the all-important fact that we are both part of a shared universe, not just in an environmental sense, but also in a somatic sense?

Let me address these concerns in seriatim. I start with the animals in our books. In Catch that Crocodile, we have a reptile that finds itself in a small town, and its presence elicits fear and excitement, as citizens try to get rid of it. Anushka Ravishankar created a gallery of characters for the book, from Dr Dutta to a pahelwan from Benaras, all of whom attempt to wrestle with the creature. And in their minds, it becomes an adversary that they need to challenge and overcome. They all fail – and Anushka’s verse ensures that these failed encounters are at once real and absurd. She does this without rendering the animal, human-like. And when a little fisher girl finally urges the crocodile to the river, we realize that the crocodile is actually a lost reptile and not the fantastic creature that excited the townsmen’s imagination.

In Alphabets are Amazing Animals, animals are construed in a series of improbable and hilarious situations, but the kind kiwis, the jolly jaguars, the odd otters that feature in the book are clearly the products of a ludic imagination. The child’s obvious interest in the animal world is what draws her to the verse, which, in turn, renders this animal universe knowable in a fantastic sort of way. While the animal is ‘humanised’, it is evident, from both text and art, that these are special animals, those that occupy worlds that are not always their habitats. This displacement of animals from their spatial worlds to ours is of course an old human trick and this book reworks it for 4 year olds – an age when the child both delights in, and wants to be part of the animal world. The animals here are not meant to be her ‘friends’ or ‘enemies’ but rather creatures in their own right, whom the child excitedly follows, by repeating the verse, staring at the page, and by tossing the improbable tale of each animal over and over in her head.

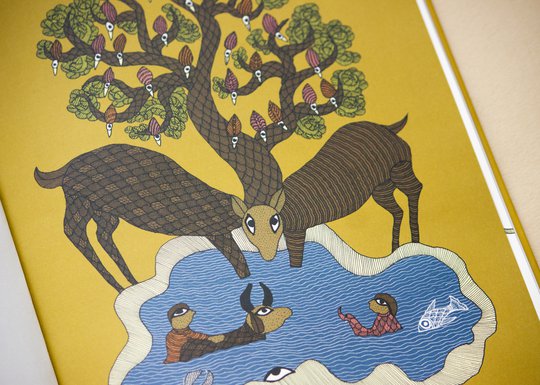

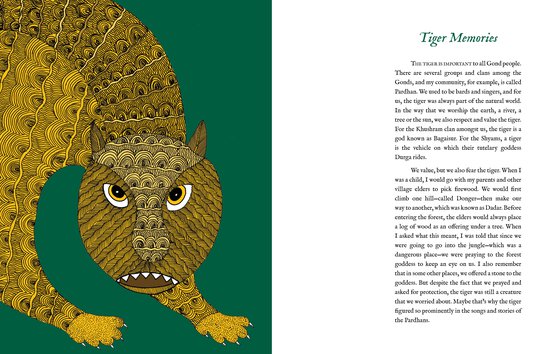

A few words about the animal art in our books: it is evident that the animals we see on the page, are really representations. This is particularly so when the artists are folk and adivasi, for many of whom, the animal world is proximate and fearful, and whose encounter with it is almost always defined by awe, fear, admiration, dread – and so animals are not ‘cute’ or representative of ecological force, rather they are creatures that one necessarily has to share the earth with, and we cannot quite escape this encounter and can only endure it. This, in fact, is the subject of Bhajju Shyam’s Alone in the Forest.

In this context, two titles, Speaking to an Elephant and Where has the Tiger Gone? seem important. The second features fables of human-tiger encounters. The art in this book makes clear that the beast is not just what we make of it, but that it can captivate and possess our imagination – we thus ‘know’ it, understand it, even, in some ways, but it is also its own creature, and we can only guess at what cannot be entirely communicated or understood. And so we try to ‘manage’ the unknown, and the consequences are not always pleasant, for either us or the beast. And the stories are open-ended, with the animal venerated in memory and the retelling of tales.

Speaking to an Elephant represents another sort of fable tradition: this goes back to the Jataka tales, in which animals act and behave in keeping with their purported characteristics, but which can be ‘read’ as morality tales. Here too, the art plays an important role in defamiliarising the beast, even as the text draws it into a shared and harmonious world. The folk and adivasi imagination neither exoticises the beast nor renders it human, rather it indicates a shared way of being which is neither easy nor avoidable, but which has to be endured and understood. Mastery is not as important here, as the acknowledgement of an uneasy coexistence.

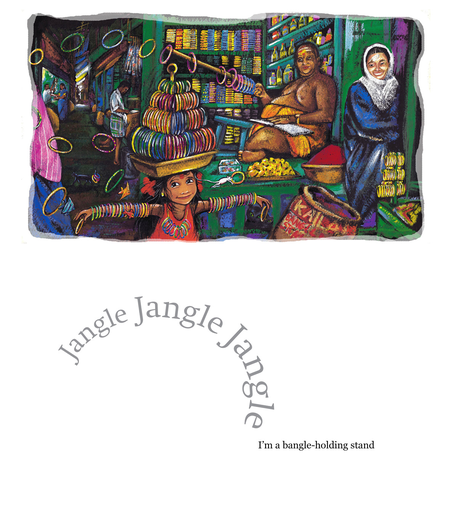

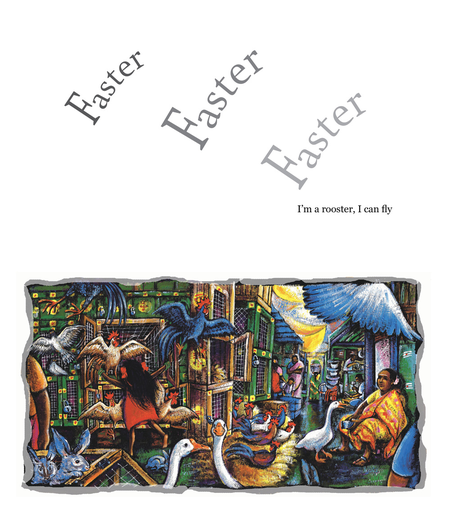

With regard to the emotions as shared intelligence in the human context: In To Market, To Market, a little girl wishes to buy this or that thing in the local market, but she is so entranced by what she sees and imagines, that she forgets to shop! The ‘discovery’ of people whom we do not usually associate with wonder and fantasy holds the book together and it is the child, who dreams up what she sees in a fantastic sort of way, captured here by the illustrations, rather than her social location that speaks to the reader.

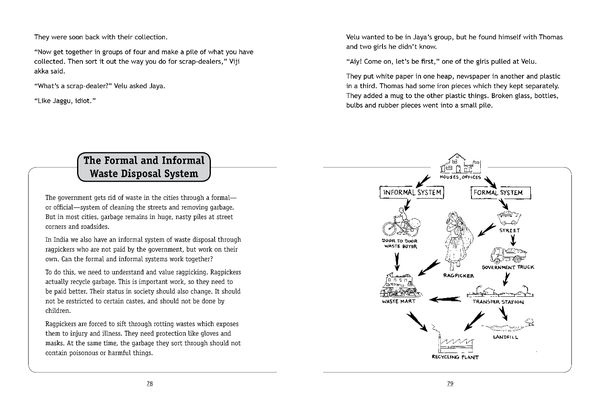

In Trash! the streetside working children do not have an easy time of it, but the narrative dwells as much on their capacity for joy, roguery… the ‘factoids’ that intersperse the narrative make sure that the reader does not get away from the structured inequality, of caste and class, that hems their lives.

In Mother Steals a Bicycle, the child narrator is both in awe of her Mother as well as skeptical of her narrative flourishes. This text is explicit in what it seeks to communicate to the child reader: the portrait of the Mother as a child, which breaks with gendered narrative convention in very many ways and complicates our understanding of childhood as well as nurture.

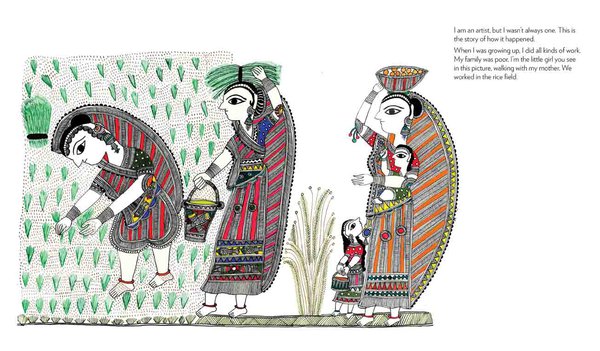

In Hope is a Girl Selling Fruit and Following my Paintbrush, the aesthetic emotion, that capacity for creation and the attendant joy that it brings, is aligned with lives that are not usually viewed as ‘creative’: portraits of the differently abled girl who signifies hope in the first, and of the household worker turned artist in the second, reference ‘shared’ intelligence in quiet but startling ways.

There are noticeably ‘urban’ or ‘cosmopolitan’ emotions in our books: and these are often marked either through dress or setting and the turn of the narrative and verse. But even when they are, the text ensures that the ‘childness’ of the child is as important a feature of the tale. This is what we have in Hic, for instance. The challenge here is, we are risking a wager: these images are not neutral, and the ‘childness’ might not always work, as much as the class and caste markers do. It is here that the book, as a composite object and its making and curation assume importance. To ensure that elusive balance between text, image and design does not take away from the primary emotion or emotions that sustain the book is a challenge.

For children, emotional expressions are also often exercises in dramaturgy and children’s literature is as caught with the performative aspects of character: in any case, representation is performative, and the challenge is to create contexts and foreground ways of seeing and being that appeal to the child’s whimsy, without fetishizing it. And also, which push the child to explore and cross boundaries, while keeping in mind her vulnerability.

Read Part Two of our conversation with Geetha.

***

V. Geetha is writer, translator, social historian, activist, and a leading intellectual from Tamil Nadu, India. Among her notable books are Gender (Stree, 2002), Towards a Non-Brahmin Millennium (with SV Rajadurai, Samya, 1998), Undoing Impunity (Zubaan, 2016) and Another History of the Children's Picture Book: From Soviet Lithuania to India (with Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, Tara Books, 2017). Her Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar and the Question of Socialism in India is forthcoming from Springer. In addition, Understory would like to acknowledge Geetha's generosity in accepting our invitation and her engagement in collective thinking, particularly with students.

5 November 2021