Ritu Menon,

Women Unlimited/

Kali for Women

On Testimony

Testimonio began as a Latin American literary genre in the 1960s, referring to first person narratives of marginalized persons. As a method, testimonies weave together instances of injustice and resistance, and are as political as they are literary. In their classic 1992 work, Testimony, Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub explored the relationship between ‘literature and testimony, between the writer and the witness’. Felman and Laub proposed to ‘read’ testimony as texts situated in the fields of literature, psychoanalysis and history. Trauma, the authors say is not an Event of the past, but a history that is ‘not over’. The genre became a way to acknowledge the violences of the 20th century.

Anthropologist Veena Das writes that her research on violence was not about the recovery of the collective self from the ghostly past, but about ‘the context of making the everyday inhabitable.’ Here, testimony is not a truth-telling practice, because testimony may also deny other kinds of remembrance. Instead, anthropology that is interested in testimony and experience opens us to the limits of the Enlightenment social contract: “we reach not the end of agreement but the end of criteria”. What is at stake is our understanding of life as we know it. In this conversation, we engage pioneering feminist publisher, researcher and biographer, Ritu Menon, to consider testimony for anthropological purposes.

We wish to explore ‘the practical hazards of listening’ by touching on areas that Menon has facilitated, in her capacity as listener, writer and publisher. In keeping with our past interviews where we explored an ‘intervention’ in the field, we recognize the importance of small feminist publishing houses that challenged official narratives and changed historiography. We have also included lengthy excerpts from books that lend themselves to field observations to encourage readers to support houses like Menon’s Women Unlimited.

This is Part One of our interview. Read Part Two here.

One

At the beginning of your book with Kamla Bhasin, Borders and Boundaries (2000), you recognize a dilemma in oral history: how to represent individual testimony. You say,

Since we are almost always in a situation where “other” people are the subject of “our” research, old hierarchies and inequalities tend to get reproduced all over again. Feminists and other practitioners of participatory research have tried to redress this imbalance somewhat by “returning” the research to their subjects or initiating some form of action that maintains continuity with them. At best, such attempts only demonstrate a sincerity of purpose and sensitivity to the larger question of power and control…

[W]e decided to use a combination of commentary and analysis, narrative and testimony, to enable us to counterpoint documented history with personal testimony; to present different versions constructed from a variety of source material.

Partition narratives show us how women’s experiences and opinions went against official policy of India and Pakistan. You focus on the figure of the ‘abducted woman’ around whom different opinions congeal,

In the Recovery Operation, Rameshwari Nehru and Mridula Sarabhai represented two opposing poles on whether or not abducted women should be recovered against their wishes. One, Rameshwari Nehru’s, was primarily a moral and ethical position; the other, Mridula Sarabhai’s, a moral and political one.

Kammoben’s ambivalence, Krishna Thapar’s zeal in getting her women married honourably and her equal distress at having to repatriate those who did not wish to go back, Mridula Sarabhai’s insistence that a woman outside her own community was dishonoured, and Rameshwari Nehru’s refusal to continue to rob women of their choice and chance of happiness, all indicate how women’s agency is situated in a contradictory way, as both complicit and transgressive in patriarchal structures. They may well subscribe to an overarching patriarchal ideology, but it was they, as women who were most familiar with the ground reality, who understood the suffering of other women in their care and were able to challenge this ideology when required.

Could you tell us how you wrote the book and what did you and Kamla Bhasin deliberate over while putting these narratives and books on partition together?

Further, I’d like to think with you about Svetlana Alexievich who has made oral history a literary genre. She was sued by her subjects, wasn’t she, for her portrayal of first-person narratives about the Soviet war in Afghanistan? It isn't just that memory is fickle, but that we have a need "for the protective shadow of a coherent narrative”, as you put it. Instead, Alexievich's heavy editorial hand ensures that a specific form of pain becomes the focus, not necessarily the individual voices. In this way, Alexievich relieves herself of the guilt of representation, and gives us something quite singular. This seems to be a little different from your own project that calls into question the sufficiency of facts, towards the "experience of historical events". By converting testimony into literature, is Alexievich giving us a way to counter tales peddled by oppressive power?

Click to read excerpts from Svetlana Alexievich's Zinky Boys.

Ritu Menon: Listening. Almost without exception what we found was that the women we spoke to were so surprised that someone actually wanted to listen to what they were saying, were interested in, and wanted to know, what they had experienced, that we just had to be patient, emote our sympathy, and keep quiet. We learnt not to interrupt, to not stem the flow, except to ask for clarification or more detail. Never to challenge or contradict with “facts”, only to affirm.

We always began with our own histories, of being born into families that had left Pakistan for India when the country was divided. Kamla was born there, I was born immediately afterwards, in Delhi. This elicited curiosity, and we were asked all sorts of questions, in turn, that we tried to answer as best we could. This broke the ice. In some cases, because we spent extended periods of time with some of the women — in one case, even staying with her in her house — we would eat together, help in the kitchen, go for a walk, even go shopping, if the woman needed to buy something. There is a way in which women can bond quite naturally, and these little breaks helped to provide some relief from listening to them recount traumatic experiences — for them and for us.

What we wrestled with: the suspicion regarding individual memory and testimony, and their disqualification as a legitimate historical resource, not “reliable” as contemporary reportage, or official records and documented, so-called objective accounts. How were we to do this, to authenticate this reportedly fickle, even treacherous, resource, without discounting and dismissing the very experience itself and the way it is remembered and recounted. How to render testimony and memory as valid, as historically significant, and in our case, as a feminist intervention in historiography.

One charge that is levelled against testimony and memory in such an endeavour is that they cannot be generalised; but as Veena Das said when we discussed this with her, we are not concerned only with “historical truth” here, but with “narrative truth” and how it allows us to understand a traumatic experience.

Our decision to counterpoint the women’s testimonies with official records and parliamentary debates was precisely to, in a way, give the lie to the official version of events and to the consequences of the decisions they made on behalf of the women; as well as to uncover and highlight the way “history” plays out in the lives of ordinary men and women. And, then, to demonstrate just how “effortlessly it conceals our past from us”, and why it might do so.

This brings us to the question of voice, and of how men and women articulate and recount their memory of what they experienced. The how and the what. Our several meetings with men and women, both, demonstrated that memory and how it presents what took place is unmistakably gendered; men and women recall the same event very differently and in different, sometimes opposing, registers. Obviously, this generalisation needs to be qualified by age, social and economic status, and impact; nevertheless it holds water.

In short, the difference was that the men spoke in the “heroic” mode, as “actors” with themselves as subjects in control (even when they clearly were not in control at all); the women spoke from a position of vulnerability. As they say, “The weak have the purest sense of history, because they know anything can happen.” The same event would have very different tellings — for instance, women remembered the details about fleeing, or about finding refuge, or about what they salvaged, about how fearful they were all the time; whereas the men would speak about their “valour” and “honour”, about “saving” their women from the rampaging mob, about how affluent they had been, how much land they had, what they had been forced to leave behind, etc. I generalise, obviously, but what interested us was the difference in tone and tenor, in how the trauma was articulated, as much as in how it was experienced.

The interviews were all done together by Kamla & myself, we transcribed the tapes together, selected the ones we would reproduce in the book, and discussed how best to write this oral history. But all the secondary and archival research, and the actual writing itself, was done by me. Every word. Yet, without the interviews and without Kamla’s particular skill in drawing the women out, we would not have had this book, in this form.

I don’t know how to compare it with No Woman’s Land (2004) — that is an edited volume, with writing by different women, non-fiction, from Pakistan, India & Bangladesh.

Your example of Svetlana Alexievich’s Zinky Boys and the device she uses of transforming testimony into literature is most instructive; but quite different from our strategy of presenting testimony, and of bearing witness, via the social workers, as a distinctively feminist response to history-writing itself. Our objective was two-fold: to counter the official and “national” memory of a traumatic event in the life of the nation; and then to interrogate the very nature and definition of that nation, that country, and the borders and boundaries it created — territorial; communitarian; social; familial; patriarchal. It is the intersection of all these that allows us to arrive at an insight into how ordinary people — in our case, women — experience and encounter epochal, history-making events.

Alexievich’s deep exploration of trauma sometimes led to her subjects being rendered speechless, and the two excerpts you have chosen illustrate that. Contrary to her experience, the women we met spoke at length, glad that someone was interested enough in what they had to say, that their voices were finally being heard. That an often life-changing experience was being brought to light, understood for what it was, and had been. For them, the past was not distant.

Two

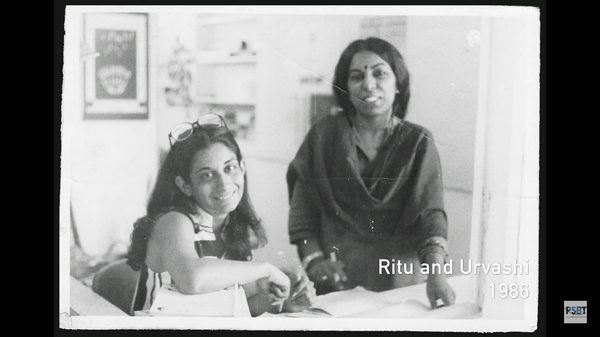

In the film Books We Made, based on your and Urvashi Butalia’s pioneering Kali for Women feminist publishing house, photographer Shebha Chhachhi speaks of documenting the women’s movement in the 80s as an alternative to the mainstream images of women, which mainly comprised the hapless victim or the jewelled maharani. Around the same time, Carolyn Forché developed a poetic genre of 'witness' to account for the violence of the 20th century in her volume Against Forgetting (1993). Forché recognized a problem in poetry - a binary between the personal and political. She says,

Poetry of witness presents the reader with an interesting interpretive problem. We are accustomed to rather easy categories: we distinguish between “personal” and “political” poems – the former calling to mind lyrics of love and emotional loss, the latter indicating a public partisanship that is considered divisive, even when necessary. The distinction between the personal and the political gives the political realm too much and too little scope; at the same time, it rends the personal too important and not important enough. If we give up the dimension of the personal, we risk relinquishing one of the most powerful sites of resistance. The celebration of the personal, however, can indicate a myopia, an inability to see how larger structures of the economy and the state circumscribe, if not determine, the fragile realm of individuality.

We need a third term, one that can describe the space between the state and the supposedly safe havens of the personal. Let us call this space “the social”... [P]erhaps we should not consider our social lives as merely the products of our choice: the social is a place of resistance and struggle, where books are published, poems read, and protest disseminated. It is the sphere in which claims against the political order are made in the name of justice.

By situating poetry in this social space, we can avoid some of our residual prejudices. A poem that calls on us from the other side of a situation of extremity cannot be judged by simplistic notions of “accuracy” or “truth to life”. It will have to be judged, as Ludwig Wittgenstein said of confessions, by its consequences, not by our ability to verify its truth. In fact, the poem might be our only evidence that an event has occurred: it exists for us as the sole trace of an occurrence. As such, there will be nothing for us to base the poem on, no independent account that will tell us whether or not we can see a given text as being “objectively” true.

If Women Unlimited occupies this space of the social, where books are the event, creating an ethic of acceptance of trauma, willingness to listen and read, it seems quite different from our contemporary experience of politics. Could you tell me about the world that brought you into feminist publishing?

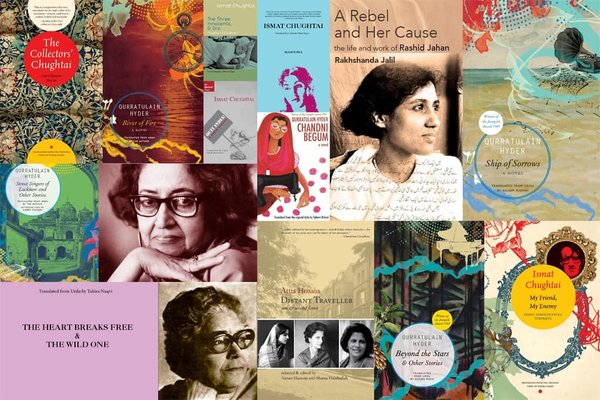

Ritu Menon: Let me say at the outset that Kali and Women Unlimited — and in fact all feminist presses worldwide — are an outcome of, and directly related to, movements for women’s liberation and their demand for equal rights and justice. Feminist publishing is publishing for social change, that is its explicit agenda.

All progressive movements are social and political, but it was the women’s movements that linked the personal to the political, saying they are indivisible. With Kali and Women Unlimited, because we came from publishing, we added professional, because we were very clear that our publishing was an intervention, both in publishing, and in the women’s movement. So it was Personal / Political / Professional.

Publishing is our activism, there is nothing neutral or unbiased about it. We are very much a part of the women’s movement, nationally, regionally and internationally, and actively involved in the issues and struggles being waged by these movements. Our links with them are forged at many levels, and we participate in them in many ways, ways that would be considered unacceptable by mainstream publishers. For instance, in the early years we drafted resolutions for groups when required; we produced activist material for them; we organised workshops and discussions and strategy meetings; we even became co-petitioners in legal cases. Very few people know that Kali was a co-petitioner in the case that led to the framing of the Supreme Court’s Vishakha guidelines on sexual harassment at the workplace.

All this was part of our publishing, all of it was an intervention.

In the early years, too, almost all our books were commissioned, often written by people who had never written before, because we took up issues as they emerged on the ground, from struggles that were being waged at the time. Our very first books dealt with the knotty question of women, religion and development (an issue that has returned with a vengeance); with the negative portrayal of women in the media; with the environment (we published Vandana Shiva's first book, Staying Alive in 1988); with identity politics and communalism; with the rise of the Hindu Right; with patriarchal attitudes and structures.

We picked up on trends as they emerged across South Asia — ethnic conflict; militancy and resistance against the state; peace; violence of all forms against women; censorship. We initiated dialogues on all these with academics and activists across borders; organised conferences that developed into books; worked collaboratively with women’s organisations, NGOs, networks in South & Southeast Asia for over two decades. And, of course, we co-published with other feminist presses across the world. This was a time of genuine internationalism in publishing, not the chilling multinationalism we see today, bereft of any inclination towards social change, quite the opposite, in fact— it is about maintaining the status quo.

Women’s studies, women’s lives. Our authors, our books, and our publishing are an intervention in the production of knowledge, in shifting the academic discourse. And in changing attitudes. So we publish everything — well, almost — that operationalises (terrible word) the personal, the political, and the progressive. We produce posters and postcards; diaries and documents; pamphlets and PhDs. We publish translations and testimonies; fiction & non-fiction; autobiographies & memoirs; and cutting edge scholarship. They are all an intrinsic part of the whole, each element a necessary addition.

Together with the international women’s movement there was a Women in Print movement, made up of editors, typesetters, designers, proof-readers, reviewers, librarians, booksellers, distributors, publishers, of course, and even printers, all of whom came together, as professional women, in solidarity and as part of the movement, to further the cause.

When I say professional, I mean that we were publishing professionals, not simply activists who ventured into publishing. It is because of our many combined years in publishing that we were able to recognise the potential of what we read and what we received as manuscripts.

We maintain those links, even though the number of feminist presses has declined and the movements have become more local. What presses like ours need today, is the support of feminist writers and academics who believe in the value of autonomy and independence, who are willing to actively and consciously practice their politics, and to work jointly for the progressive social change that we all want to see.

Feminist publishing has more or less disappeared, apart from say, at most, 8-10 actively feminist and independent presses, in the world. You could say it has been successfully “mainstreamed”; for me, it means that feminist publishing’s links with the women’s movement have become increasingly tenuous, and that it is no longer the first choice for feminist writers. The reasons for this are many and complicated, it would be too much to explain in this response. I have written about it elsewhere, of course.

About Address Book (2021): I didn’t consciously decide anything, I wrote what I was thinking about and feeling during this enforced immobility, and the kinds of memories that were triggered as I looked for the contacts of a couple of publishing colleagues I had lost touch with over the years. The conversation between Diary and Address Book was organic and inevitable, they circled back to each other almost seamlessly. Not artlessly, because I am aware of how a memoir, or recall and reminiscence, are shaped, but because Time itself became a consideration. The Address Book and the times/s it encapsulated were counterpointed against present time, that seemed suspended by comparison. The dynamism of the former, the involuntary stasis of the latter. That time of hope and the belief that publishing for social change was possible, and a time of genuine internationalism, and now, this time of isolation.

Three

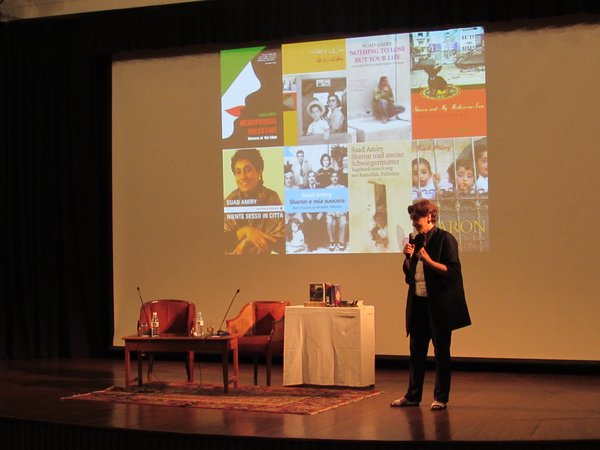

Thinking within an ethnography of devastation and fatigue, would you speak about your special rubric, Arabesque, based on writing from West Asia, which is also about border crossings. The expressions you publish are unusual: novels of hallucinations, blogs, geo-political menopause…

I was surprised by this sustained and wonderful series of novels and testimony, so affordable and published at home, as it were. As I read these books, I wonder if you are a publisher of inhospitality, made possible by feminist friendship, listening and laughter. In Address Book, you quote one of your writers, Haifa Zangana: Is sadness the first and last resting place?

On the one hand, these books voice the violent secrets within Kantian ideas of cosmopolitanism, perpetual peace and anthropology. On the other, the books remind me of the mythical promise of the 1955 Bandung conference, where weak, newly decolonized countries came together in trust in an unprecedented way. Sukarno declared that it was the first time in the history of mankind that coloured peoples were coming together. In what way does Women Unlimited insert itself into the historical links with West Asia?

From winner of the Naguib Mahfouz Medal in Literature Hoda Barakat’s Tiller of Waters, we have this moving passage about the narrator’s mother who came from Egypt,

For until the very last years of her life my mother insisted that her voice was the most beautiful of female voices to ever exist. She never quit training it, priming herself for that operatic debut. But at the point where her preparations became truly elaborate, accompanied by her changeable narratives as she took up her cosmetic pencil to redraw the lineaments of her face, I was seized with a terrible anxiety for her. Surely, I thought, my mother was growing feeble-minded with age. But I soon began listening to her stories differently, questioning myself, sceptical of my own presuppositions. After all, had there ever been a time when my mother dwelt in reality? Had anyone every been able to claim that in her youth she had told only the truth? Who could say that her tales, as variable as they were now in her old age, were not for the most part true, that they did not record events that had actually taken place?

In another book, Suad Amiry’s Menopausal Palestine, which revolves around CRIME: Committee of Ramallah Independent Menopausal Enterprise, we read,

Flora, a self-hating PLO and good poker player, who hardly reveals her private life, spoke up coolly: "I think menopause is a middle class professional women's phenomenon. Look at women in villages and refugee camps. They accept their age, they accept their wrinkles, they accept that there is no more sex in their lives, they accept they are losing authority and power, and hence act accordingly. Unlike us, at fifty plus, we want to look thirty-five, that's why we are anxious, angry and frustrated. We refuse to accept new realities, we want eternal youth and power. It doesn't work."

It was no longer clear to me whether Flora was referring to botox, Hamas or menopause. As the long night dwindled, CRIME members got exhausted and all issues, arguments, clashes and flashes began merging: all were anxious, all deemed to be in total denial, and all were having difficulty accepting new realities: whether they were wrinkles, ageing or Hamas.

All seemed to be having difficulties with expression, memory and power.

The day after, Hamas had a sweeping victory.

Experts say: Menopause is a wake-up call for a new phase in your life.

And I say: So is Hamas.

Two wake-up calls may be more than most people can handle."

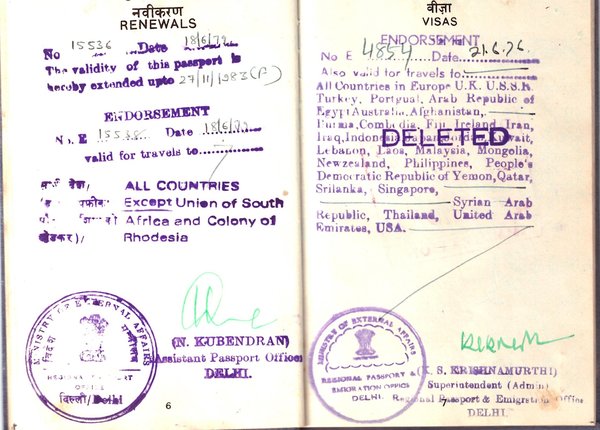

Ritu Menon: The first passport I ever had, when I was seven years old, had a stamp in it which said: “Not valid for travel to South Africa and Israel”; the same stamp appeared in all Indian passports till 1991, when apartheid was abolished in South Africa, and after 1992, when India opened an embassy in Israel for the first time after it became independent in 1947.

Scan of Ritu Menon's passport: South Africa & Rhodesia are mentioned specifically, and Israel is not included in the list of countries on the opposite page. That list was deleted in 1979, but as Israel had no representation in India, travel to that country was still not possible. An Indian Embassy was established in Israel only in 1992, and an Israeli Embassy in India in the same year. Image: Ritu Menon

That stamp was India’s statement of solidarity with the original, indigenous people of South Africa against an abhorrent custom of segregation, based on skin colour, practiced by the colonising Dutch; and a statement of solidarity with the displaced original inhabitants of Palestine by Israel, based on an equally abhorrent Occupation and confiscation of their land, and a blatant denial of their right to live as equals in it. It was also a commitment made to all former colonised peoples based on the powerful principle of non-alignment with the Cold War of the two super powers then, the US and the Soviet Union.

India’s links with West Asia are ancient and modern, established long before both regions were colonised, and long after they attained freedom; but it is ironical that despite this political solidarity we are more or less ignorant about their literary and cultural production. We know little about their everyday lives, as unfortunately, our gaze is turned towards the erstwhile coloniser and its literary and cultural products.

There can be no other country like Palestine, it is unique. Unhappily so, but nevertheless. In 2010 I visited Palestine as a participant in the Palestine Festival of Literature, and saw and heard, at first hand, the astonishing energy and creativity that was evident at every turn, all the more extraordinary for the fact that it found expression in circumstances of extreme repression. I decided then that while political support, at one remove, was necessary, it was also important for us to engage with Palestinians and the rest of West Asia, with Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Morocco, Iraq, via their intellectual and creative endeavours.

And PalFest is unique, because its character is determined by the peculiar and oppressive reality of how Palestinians live under Occupation. They /we cannot move freely. You pass through any number of checkpoints to travel a few kilometres. You come up against a Wall. Literally. You have to produce, and prove, your identification at every step. You cannot go to Gaza. In Hebron, the city is divided into zones that are classified according to security “risks”. There are snipers on rooftops.

This being so, the Festival travels to people, rather than the other way around, from city to city. So we went to Jerusalem, Nablus, Bethlehem, Hebron, Ramallah. Everywhere the same enthusiastic response, the sheer joy of being able to listen to writers from other parts of the world, the animated faces, the creativity and grace under pressure. The humour. In the only museum of captivity that I have ever seen, a slogan: “I didn’t ask to be born in Palestine, I just got lucky.”

In universities the students embodied resistance, and resilience. The questions they asked, the comments they made, all demonstrated a heightened awareness of their situation, of how they negotiate it on a daily basis.

Thus did Arabesque come into being. It has been one of the most worthwhile things we have done as a feminist publisher, and the links we have been able to forge across that region are mong the most precious. Over the years that followed we invited the writers Suad Amiry, Radwa Ashour, Ahdaf Soueif, Hoda Barakat, Haifa Zangana and Jean Said to India, so that we could listen to what they said and wrote, at first hand. We took them to Bombay, Calcutta, Chennai, Bangalore, and everywhere they spoke, they were greeted with warmth and enthusiasm. In 2014-15 we organised a festival, Palestine in India, and this time, we included booksellers and publishers, in addition to writers, 10-12 in all. They interacted with the general public, of course, but they also spoke to students in colleges and universities, as well as to civil society groups working on Palestine and on human rights.

I, personally, am a member of the Indian Campaign Against the Cultural and Academic Boycott of Israel, and a strong supporter of the international BDS movement. Arabesque is possibly our most openly political act as a publisher. And the writers we have published and invited to India are a living testament to the struggle they are engaged in, on a daily basis, and to its literary expression — to the power of the word.

Click to read Part Two of our conversation with Ritu Menon.

***

Ritu Menon co-founded Kali for Women, India’s first feminist press, in 1984, and is founder-director of Women Unlimited, an associate of KfW. She is the author of several books, among them the groundbreaking Borders & Boundaries: Women in India’s Partition; Out of Line: a literary and political biography of Nayantara Sahgal; Loitering With Intent: Diary of a Happy Traveller; and editor of a number of anthologies of prose, poetry and memoirs. Her latest books are ZOHRA! A Biography in Four Acts and Address Book: A Publishing Memoir in the time of COVID. She was awarded the Padma Shri in 2011.

30 March 2022