Ritu Menon,

Women Unlimited/

Kali for Women

Part Two

Understory continues our conversation on testimony with Ritu Menon, founder and feminist publisher of Kali for Women/Women Unlimited.

Read Part One here.

Four

I’d like to focus on a book you published, Krishna: Living with Alzheimer’s by Ranabir Samaddar in 2015. I am familiar with Prof. Samaddar’s writing on the postcolonial state, refugee and forced migration. In this account of caring for his wife, Dr. Krishna Samaddar, the solitary helplessness and the anguished love, which belongs to the writer alone, resonates with the reader in our medicalized times.

I read Anne Boyer’s The Undying, an account of a woman who endured allopathic cancer treatment, where she says,

I hate to accept, but do, that cancer’s near-criminal myth of singularity means any work about it always resembles testimony. It will be judged by its veracity or its utility or its depth of feeling but rarely by its form, which is its motor and its fury, which is a record of the motions of a struggle to know, if not the truth, then the weft of all competing lies.

I imagine that Prof. Samaddar would agree with this testimonial. As a care-giver, he provides an alternative to acknowledge his wife’s autonomous subjectivity, even as it decreased, that takes us through these ‘motions of struggle’. Hence, a feminist memoir on illness is not only a testimony of care, but also an uncovering of the ‘fascist psychology’ of medicine, and its weft of lies. Feminist publishing, it seems, performs a similar act of care. Do you think such a book resonates, then, with the limits of testimony, and where would that take us?

Click to read an excerpt from Krishna: Living with Alzheimer's.

Ritu Menon: For some time now, I have been trying to develop a series on mental health, first-person accounts of a state of mind that is difficult to write about without guile or artifice, without dramatising it. It is manifest in different forms, subtle and complex, and evades easy telling.

Some years ago we published an account by an extraordinary young woman, of her experience of schizophrenia, and how she learnt to live with it, and manage it, and creatively transform it, without medicalising her condition — or her health and well-being. Her book is called Fallen Standing: My Life as a Schizophrenist. This is a word she coined, saying if you can be an artist or a dentist, I can be a Schizophrenist.

The manuscript was sent to me as a series of emails, one every Monday morning, if she felt up to writing it. There were weeks when nothing arrived, either on a Monday or on any other day. And one Monday, I received an email with just one word in it, repeated close to a hundred times: Alone. The author, Reshma Velliappan, is one of the bravest women I know, and one of the most creative, and Fallen, Standing is a rare testimony by someone who refused to let herself be stigmatised or victimised. It is also an amazing story of recovery, in every sense of the word.

When Ranabir da — whom I have known for a very long time and whom I regard as one of the most original thinkers in India today — called to say he had written this account of Krishna di’s Alzheimers and wanted us to publish it, I agreed immediately. “It’s a small book,” he said, “it may not suit you,” but I knew, without reading one word of it, that it was just the kind of account that suited us very well.

You ask, how did we come to publish it? Here is why: a first-person account of Alzheimer’s is an impossibility, the condition does not allow it. Second-hand accounts, if any, are likely to be either overly “medical”; or overly sentimental. Ranabir Samaddar’s Krishna is unusual and remarkable because he lays bare his vulnerability in the face of this health “crisis”. Very few men are able to expose themselves in this way, to recognise their helplessness in dealing with a condition like this, and to write in this vein, without self-congratulation or self-pity. And there are very few who will reveal the intimacy of their marriages and accept culpability in the way he has.

It is astonishing that he has been able to combine his lifelong commitment, intellectual as well as political, to what he calls the ethics of care, with a compassionate consideration of what it means to live with Alzheimer’s, at the same time as he dismantles the medical response to it. And he does so without once displacing Krishna, she remains foregrounded throughout. So yes, he bears witness, and he writes a testimony.

Ranabir da has written a quintessentially feminist account. How could we not publish it?

Five

Could we come to your fondness for the genre of the biography? You have also published at least one biography (that I have read): Vasanth Kannabiran’s Sathyavathi: Confronting Caste, Class and Gender.

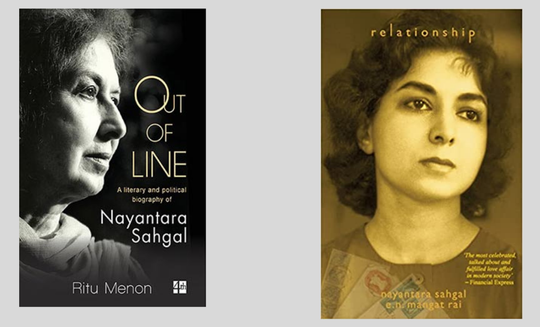

Here, I’d like to end with a biography that bears a curious relationship to your work on partition. In Out of Line, your literary and political biography of Nayantara Sahgal, you give voice to that which does not have a name. In effect, you attend to multiple displacements, but this time through form: you move between Sahgal’s private and public life to novelistic witness of the nation, and the consolation of letters. Do you think of letters as not only a path to the private, but which strike at actual life? How did you come to biography? I read the book as an extraordinary work of craft between two writers and two readers. You write,

The schizophrenic imagination, Nayantara has said, is rooted in a particular subsoil but doesn’t belong to any particular context, has no single home. What it has is a multiple tradition that it can never disown, which usually means that an individual with such an imagination ends up being a misfit.

And finally, I wanted to thank you for publishing a selection of letters in 1994, between Nayantara Sahgal and EN Mangat Rai, from about six thousand. Rather than see them in historical and biographical light, they helped me revive for myself the sustained pleasure of epistolatory exchange, over email today, that has fallen by the wayside in our times of quick and short phone messages.

Ritu Menon: Biography, or personal history, is also history. Lives are lived in a social, political, cultural context, every day is an element in history-making and every life partakes of, and lives in, that historical time. How is that life to be written or told? What about it is of significance? How did the biographer’s subject locate herself and her life in the times she lived in? As active participant, observer, or bystander? As consciously engaged or not? What about that life is notable, unusual or remarkable?

First, the very fact that hardly any mainstream publishers have bothered to commission biographies of so-called “important” women is an indication of the gender gap in this genre. Again and again, relatively minor male bureaucrats, politicians, actors, sportsmen, even noblemen and their hangers-on, are privileged over women who have played an important role in the country’s social and political life. This is one major reason why we decided to publish as much as we can on them.

Second, it is very difficult to obtain primary and secondary source material on “unimportant” people, male or female, so unless they happen to be alive (like Sathyavati) and one can interview them at length and in depth, they are not easy to biograph.

I am interested in women’s lives, and particularly in those women whose lives intersect with the life of their societies or countries in specific ways. Maybe even in momentous ways. Then, I am interested in exploring how that life may be written / or is told from a feminist perspective. What is it that I bring to bear on my recounting of it that is gendered? What are my responsibilities towards my subject? What do I reveal, how do I decide what is relevant, and what needs to be highlighted? And so on.

My interest lies in exploring how a feminist biography differs from biographies in general. How does one approach one’s subject? What decisions does one make regarding the private and the public; what responsibilities does one have towards the life one is writing? How much to reveal, how much is relevant, how much just speculation or gossip — or, worse, unnecessary detail — that adds little to what you want to highlight. Why and how is writing a women’s lives different from men’s? Is it at all so different? Clearly it is, because the circumstances that shape their lives are very different, and all lives are lived in context — social, political, familial, private, public, domestic.

If I have been able to do this, that would be my intervention.

In Nayantara Sahgal I found that unexpected overlap, or superimposition, if you like, between her life and the life of the nation, as everything she wrote was about her own, personal and political, engagement with India, from pre-to post-Independence. It was also her comment on how free India was evolving, how this bold experiment in nation-building was unfolding, how India was defining herself and taking her place in the world. India was her material, and being who she was, she was uniquely placed to witness history in the making.

In this sense, and moving through form, as you say, she was writing in different registers: novels; autobiography; newspaper columns; reportage; biography; letters. Each was uniquely personal, as well as literary and political. She herself did not think of her novels as overtly political; “for that I have journalism” she said. Yet there is no way her novels can be read without reference to what was happening in the country — and in her own life.

You ask about Nayantara’s correspondence with E.N. Mangat Rai, whether the letters are ''not only a path to the private, but which strike at actual life.” Indeed, that is what they are. Reading them, almost all 6,000 of them, I was struck repeatedly by how deeply and unguardedly intimate they are, and how suffused with the political. And in this political, I include gender relations, and the domestic space, as intrinsically political. Making this correspondence public was an extraordinary act of courage and honesty.

It was a privilege to have been able to publish them.

Read Part One of our conversation with Ritu Menon here.

***

Ritu Menon co-founded Kali for Women, India’s first feminist press, in 1984, and is founder-director of Women Unlimited, an associate of KfW. She is the author of several books, among them the groundbreaking Borders & Boundaries: Women in India’s Partition; Out of Line: a literary and political biography of Nayantara Sahgal; Loitering With Intent: Diary of a Happy Traveller; and editor of a number of anthologies of prose, poetry and memoirs. Her latest books are ZOHRA! A Biography in Four Acts and Address Book: A Publishing Memoir in the time of COVID. She was awarded the Padma Shri in 2011.

30 March 2022